In the United States the Saints were becoming more visible throughout the nation, and in the 1960s there was more commentary on the involvement of the Church and its leaders in public affairs than in any period since 1920. An unusual number of public issues arose in which the Church seemed to have a direct interest, and for that reason this was not only a period of growth and correlation but also one of controversy and some public criticism.

During the presidential campaign of 1960, the public press seemed insistent upon interpreting the political statements of the President of the Church as somehow reflecting Church policy rather than private opinion. When the Republican candidate, Richard M. Nixon, visited Salt Lake City, President David O. McKay was heard to tell him "we hope you are successful. " This comment was quickly picked up in the national press and interpreted as an official endorsement. President McKay quickly clarified his statement by declaring that he was speaking "as a personal voter and as a Republican, " but certainly not for the Church as a whole. Unfortunately, the correct explanation did not receive nearly as much publicity as the original news story.

More controversial was the debate over what methods should be employed to combat the growth of communism. Latter-day Saints along with other Americans were convinced that communism posed a threat to the American economic and political system, as well as to religion, and that communists were involved in various subversive activities. President McKay affirmed that the Church was opposed to communism, and encouraged the Saints to help prevent its spread. But a number of nationally prominent Saints were also active in anti-communist groups that seemed to go too far in making unproven accusations and defaming the character of other Americans by implying they were involved in subversive activities. Such groups also tended to oppose any extension of the power of the federal government, on the grounds that this would lead inevitably to communism. Some Saints even created the impression, perhaps unintentionally, that the Church officially endorsed conservative political causes. The First Presidency continually issued statements reiterating that the Church took no position on partisan politics, prohibiting the use of church buildings for political purposes, and making it clear that even though the Church opposed communism, it could not condone the methods sometimes employed by anti-communist individuals and groups.

Despite its efforts to remain aloof from partisan politics, the Church nevertheless took sides on a few significant political issues in the 1960s. In each case Church leaders felt a moral obligation to take a stand, though they were occasionally criticized for "dabbling in politics. " One issue was liquor by the drink, which came before Utahns in 1968. The Church not only took a public stand against it but openly used its priesthood organization to distribute literature and circulate petitions. Significantly, opposition to the Church's stand was not construed as disloyalty to the Church. The First Presidency also supported Sunday closing laws, upheld the spirit of civil rights legislation (although it did not take sides on specific bills), and favored the protection of state right-to-work laws.

Perhaps the most delicate public issue involving the Church in the 1960s was civil rights. In the United States racial strife reached a peak as black citizens demanded an end to racial discrimination in every form. Prejudice and the tradition of segregation led to violence in many parts of the country, though in the long run considerable constructive legislation provided a legal basis for an end to discrimination in housing, education, employment opportunity, and all other public aspects of American life. In the turmoil every institution in America was reexamined, and for the first time many people became aware of the Church's policy of not ordaining blacks to the priesthood. This was interpreted by some people in the 1960s as a sign of racial prejudice and discrimination, and the Church quickly came under fire in national periodicals and from civil rights groups. In the late 1960s protest rallies were held in Salt Lake City, and delegates from many civil rights groups sought audiences with Church leaders in an effort to get them to change the policy. Brigham Young University athletic teams were picketed and harangued while on road trips, and at some games anti-Mormon riots broke out. Some schools severed athletic relations with BYU.

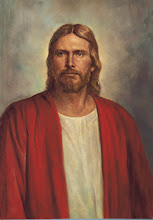

The new Church Office Building, completed in 1972. (LDS Church)

The Church's response was that it could not change the policy without divine revelation authorizing it to do so. Church leaders reminded critics that the issue was a matter of religious faith and that those who did not share that faith should not attempt to dictate policy to the Church. The priesthood policy had nothing to do with the position of individual members on the matter of civil rights; the Saints were duty-bound to support the principle of full civil rights for all people. In 1963 President Hugh B. Brown of the First Presidency declared in October general conference:

We believe that all men are the children of the same God, and that it is a moral evil for any person or group of persons to deny any human being the right to gainful employment, to full educational opportunity, and to every privilege of citizenship, just as it is a moral evil to deny him the right to worship according to the dictates of his own conscience. . . .

We call upon all men, everywhere, both within and outside the Church, to commit themselves to the establishment of full civil equality for all of God's children.

On December 15, 1969, partly because protests still continued, the First Presidency issued another official statement. It said, "We believe the Negro, as well as those of other races, should have his full constitutional privileges as a member of society, and we hope that members of the Church everywhere will do their part as citizens to see these rights are held inviolate. " fn

(James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 2nd ed., rev. and enl. [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1992], 621 - 622.)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment