Joseph B. Wirthlin, “Fruits of the Restored Gospel of Jesus Christ,” Ensign, Nov 1991, 15

My brethren and sisters, I’m sure that all of us have been honored to be in the presence of President Ezra Taft Benson, the President of the Church, our prophet. I’ve loved him and respected him all of my life, as I’m sure you have.

Throughout the ages, the Lord has referred to his people, those who love him and keep his commandments, in words that set them apart. He has called them a “peculiar treasure” (Ex. 19:5), a “special people” (Deut. 7:6), “a royal priesthood, an holy nation” (1 Pet. 2:9). Scriptures refer to such people as Saints. As the Savior taught, “by their fruits ye shall know them.” (Matt. 7:20.)

In sharp contrast to those who live by gospel principles, I see accounts of people who either ignore or don’t understand these principles. Some do not live the gospel standards and live in sin, evil, dishonesty, and crime. The result is untold misery, pain, suffering, and sorrow.

I am reminded of the Savior’s teachings when he declared:

“Therefore whosoever heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them, I will liken him unto a wise man, which built his house upon a rock:

“And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock.

“And every one that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand:

“And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell: and great was the fall of it.” (Matt. 7:24–27.)

This analogy teaches us an important lesson. We cannot have the fruits of the gospel without its roots. Through revelation, the Lord has established those roots—distinctive principles of the fulness of the gospel. They give us direction. The Lord has taught us how we should build our lives on a solid foundation, like a rock, that will withstand the temptations and storms of life.

May I give you some of the major principles of the gospel.

The Godhead

One distinctive principle is a true concept of the nature of the Godhead: “We believe in God, the Eternal Father, and in His Son, Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Ghost.” (A of F 1:1.) The Godhead consists of three separate, distinct personages who are one in purpose. The Father and the Son have tangible bodies of flesh and bone while the Holy Ghost is a personage of spirit.

God truly is our Father, the Father of the spirits of all mankind. We are his literal offspring and are formed in his image. We have inherited divine characteristics from him. Knowing our relationship to our Heavenly Father helps us understand the divine nature that is in us and our potential. The doctrine of the fatherhood of God lays a solid foundation for self-esteem. The hymn titled “I Am a Child of God” (Hymns, 1985, no. 301) states this doctrine in simple terms. Can a person who understands his divine parenthood lack self-esteem? I have known people who have a deep, abiding assurance of this truth and others who understand it only superficially and intellectually. The contrast in their attitudes and the practical effect of these attitudes in their lives is remarkably apparent.

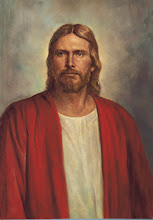

Knowing that Jesus Christ is the firstborn Son of God in the spirit and the Only Begotten Son in the flesh gives a far more noble and majestic view of him than if he were just a great teacher or philosopher. He is our Lord, the Redeemer of all mankind, our Mediator with the Father. Because of his love for us, he has atoned for the sins of the world and has provided a way for the faithful to return to our Heavenly Father’s presence.

“He is the greatest Being to be born on this earth—the perfect example. … He is Lord of lords, King of kings, the Creator, the Savior, the God of the whole earth. … His name … is the only name under heaven by which we can be saved.

“He will come again in power and glory to dwell on the earth, and will stand as Judge of all mankind at the last day.” (Bible Dictionary, s.v. “Christ.”)

He stands as the head of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. We should be everlastingly grateful to him. We should love him with all our hearts and should follow his example.

The Holy Ghost, the third member of the Godhead, is a revelator (see History of the Church, 6:58); he reveals the word of God. He provides the convincing witness that the gospel is true and gives a person a testimony of the divinity of Jesus Christ. He guides us in our choices and in our search for truth.

Resurrection

Next I turn to our assurance of a literal resurrection, the uniting, after mortal death, of the spirit with a body of flesh and bone. Jesus, the first on this earth to be resurrected, made the resurrection a certainty for all mankind. This reality is a center point of hope in the gospel of Jesus Christ. (See 1 Cor. 15:19–22.)

I have seen the contrast between those who have spiritual confidence in the resurrection and others who are confused and uncertain about our postmortal condition. I was inspired by one mother who faced the untimely death of a two-year-old daughter with serenity, despite her deep sorrow. She attributed the peace she felt to her faith in a merciful God and in life everlasting. She was confident that this sweet child was encompassed in the arms of God’s love and that she and her daughter would be together again.

Parenting

In the Lord’s plan, parents are to teach their children during the impressionable and formative years when they develop attitudes and habits that last a lifetime. President Brigham Young wisely recognized that “the time of youth and early manhood is the proper time” to gain mastery over bodily appetites and passions. He warned that “the man who suffers his passions to lead him becomes a slave to them, and such a man will find the work of emancipation an exceedingly difficult one.” (Letters of Brigham Young to His Sons, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1974, p. 130.) We can be so grateful for principles that provide positive, spiritual reinforcement for parental teachings and that direct young people away from the pitfalls that Satan has strewn along the path of adolescence and young adulthood.

Word of Wisdom

The Word of Wisdom was revealed to the Prophet Joseph Smith in 1833. This revelation has been scrutinized and ignored, attacked and defended, ridiculed and praised. Meanwhile, faithful Saints have observed it as a token of their obedience to God. For many years, they could obey it only on faith, in much the same spirit that Adam offered sacrifice. An angel asked him, “Why dost thou offer sacrifices unto the Lord? And Adam said unto him: I know not, save the Lord commanded me.” (Moses 5:6.) Early members of the Church obeyed the Lord’s counsel without the benefit of present medical knowledge, which has validated the physical benefits of their obedience. We now know by scientific evidence what the Saints have known by revelation for 158 years.

Imagine the results we would see if the total populace were to live this law of health and never abuse their bodies with alcoholic beverages, tobacco, and other harmful substances. What magnitude of decline would we see in automobile accidents, illness and premature death, fetal defects, crime, squandered dollars, broken homes, and wasted lives resulting from alcohol and other addictive drugs? How much would lung cancer, heart disease, and other ailments caused by cigarette smoking decrease? The fruits of this commandment bring innumerable blessings.

Members of the Church have obviously been blessed with health and spirituality by being obedient to this commandment.

Welfare Principles

A sure indicator of true religion is a concern for the poor of the earth. This leads us to provide for their needs by acts of charity. I quote James: “Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this, To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction, and to keep … unspotted from the world.” (James 1:27.)

Stated simply, charity means subordinating our interests and needs to those of others, as the Savior has done for all of us. The Apostle Paul wrote that of faith, hope, and charity, “the greatest of these is charity” (1 Cor. 13:13), and Moroni wrote that “except ye have charity ye can in nowise be saved in the kingdom of God” (Moro. 10:21). I believe that selfless service is a distinctive part of the gospel. As President Spencer W. Kimball said, welfare service “is not a program, but the essence of the gospel. It is the gospel in action.

“It is the crowning principle of a Christian life.” (Ensign, Nov. 1977, p. 77.)

The Church does substantial but perhaps little-known humanitarian work in many places in the world. Our ability to reach out to others is made possible only to the extent that we are self-reliant. When we are self-reliant, we will use material blessings we receive from God to take care of ourselves and our families and be in a position to help others.

Comment on the principle of self-reliance may seem merely to echo the obvious, but it runs counter to the trends in our society that shift responsibility to others. Many Saints have been spared suffering because they have lived by this principle.

The foundation of self-reliance is hard work. Parents should teach their children that work is the prerequisite to achievement and success in every worthwhile endeavor. Children of legal age should secure productive employment and begin to move away from dependence on parents. None of us should expect others to provide for us that which we can provide for ourselves.

Missionary Work

Missionary work was a distinct part of the Savior’s mortal ministry. This is also true today. The Savior commanded, “Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature.” (Mark 16:15.) His disciples, especially Paul, proclaimed the gospel message widely in the years following the Savior’s crucifixion. In 1831, the Lord revealed through the Prophet Joseph Smith, “The voice of the Lord is unto all men, and there is none to escape; and there is no eye that shall not see, neither ear that shall not hear, neither heart that shall not be penetrated.” (D&C 1:2.)

Today more than 44,000 missionaries are working to fulfill the divine mandate to preach the gospel. They bless the people they teach by acquainting them with the fulness of the restored gospel. They bless themselves by the dramatic growth and maturity that come during a mission. Every worthy young man should go on a mission. Also, worthy young women and couples of the Church can give invaluable service in the mission field. They all serve as the emissaries of the Lord. We thank them most sincerely.

Chastity

Another distinctive characteristic of the gospel is the adherence to the Lord’s law of chastity. From ancient times to the present, the Lord has commanded his people to obey this law. Such strict morality may seem peculiar or outdated in our day when the media portrays pornography and immorality as being normal and fully acceptable. Remember, the Lord has never revoked the law of chastity.

Temple marriage vows increase the depth of faithfulness between husband and wife.

Obedience to the law of chastity would diminish cries for abortion and would go a long way toward controlling sexually transmitted disease. Total fidelity in marriage would eliminate a major cause of divorce, with its consequent pain and sadness inflicted especially upon innocent children.

Of course, members of the Church have their share of faults and weaknesses, but we see abundant evidence that living the gospel does help the Saints to become better. As more people commit themselves to living the gospel with all their heart, might, mind, and strength, they will be examples to their families and friends.

How blessed we are to understand and to have the privilege of living by the sacred, eternal principles of the gospel of Jesus Christ. They are true. They will lead us along the only safe course to happiness, which is “the object and design of our existence.” (Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, p. 255.)

Conclusion and Promise

In conclusion, let me offer this advice and promise. Never be ashamed of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Partake of the sacrament worthily. Always remember our Lord and Savior. Never defame his sacred name. Do not ridicule the sacredness of the holy priesthood and the ordinances of the gospel. If you honor this counsel, the spirit of rebellion will never come into your hearts.

You will be blessed as was Alma, who said:

“I have labored without ceasing … that I might bring them to taste of the exceeding joy of which I did taste. …

“Yea … the Lord doth give me exceedingly great joy in the fruit of my labors;

“For because of the word which he has imparted unto me, behold, many have been born of God, and have tasted as I have tasted.” (Alma 36:24–26.)

In addition, if you will sustain the Lord’s anointed, your confidence in them will wax strong. Your families and your posterity will be blessed and strengthened. The abundant fruits of the gospel will enrich your lives. Peace and unity will fill your hearts and homes.

My brothers and sisters, your leaders of the Church love you and labor to bring you the fruits of the gospel that you may taste as we have tasted. May you feel that marvelous joy of God’s love and his blessings in your life, I pray in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Showing posts with label Restoration. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Restoration. Show all posts

Sunday, October 12, 2008

Apostasy and Restoration

Dallin H. Oaks, “Apostasy and Restoration,” Ensign, May 1995, 84

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has many beliefs in common with other Christian churches. But we have differences, and those differences explain why we send missionaries to other Christians, why we build temples in addition to churches, and why our beliefs bring us such happiness and strength to deal with the challenges of life and death. I wish to speak about some of the important additions our doctrines make to the Christian faith. My subject is apostasy and restoration.

Last year searchers discovered a Roman fort and city in the Sinai close to the Suez Canal. Though once a major city, its location had been covered by desert sands and its existence had been forgotten for hundreds of years (see “Remains of Roman Fortress Emerge from Sinai Desert,” Deseret News, 6 Oct. 1994, p. A20). Discoveries like this contradict the common assumption that knowledge increases with the passage of time. In fact, on some matters the general knowledge of mankind regresses as some important truths are distorted or ignored and eventually forgotten. For example, the American Indians were in many respects more successful at living in harmony with nature than our modern society. Similarly, modern artists and craftsmen have been unable to recapture some of the superior techniques and materials of the past, like the varnish on a Stradivarius violin.

We would be wiser if we could restore the knowledge of some important things that have been distorted, ignored, or forgotten. This also applies to religious knowledge. It explains the need for the gospel restoration we proclaim.

When Joseph Smith was asked to explain the major tenets of our faith, he wrote what we now call the Articles of Faith. The first article states, “We believe in God, the Eternal Father, and in His Son, Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Ghost.” The Prophet later declared that “the simple and first principles of the gospel” include knowing “for a certainty the character of God” (“Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons, 15 Aug. 1844, p. 614). We must begin with the truth about God and our relationship to him. Everything else follows from that.

In common with the rest of Christianity, we believe in a Godhead of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. However, we testify that these three members of the Godhead are three separate and distinct beings. We also testify that God the Father is not just a spirit but is a glorified person with a tangible body, as is his resurrected Son, Jesus Christ.

When first communicated to mankind by prophets, the teachings we now have in the Bible were “plain and pure, and most precious and easy” to understand (1 Ne. 14:23). Even in the transmitted and translated version we have today, the Bible language confirms that God the Father and his resurrected Son, Jesus Christ, are tangible, separate beings. To cite only two of many such teachings, the Bible declares that man was created in the image of God, and it describes three separate members of the Godhead manifested at the baptism of Jesus (see Gen. 1:27; Matt. 3:13–17).

In contrast, many Christians reject the idea of a tangible, personal God and a Godhead of three separate beings. They believe that God is a spirit and that the Godhead is only one God. In our view, these concepts are evidence of the falling away we call the Great Apostasy.

We maintain that the concepts identified by such nonscriptural terms as “the incomprehensible mystery of God” and “the mystery of the Holy Trinity” are attributable to the ideas of Greek philosophy. These philosophical concepts transformed Christianity in the first few centuries following the deaths of the Apostles. For example, philosophers then maintained that physical matter was evil and that God was a spirit without feelings or passions. Persons of this persuasion, including learned men who became influential converts to Christianity, had a hard time accepting the simple teachings of early Christianity: an Only Begotten Son who said he was in the express image of his Father in Heaven and who taught his followers to be one as he and his Father were one, and a Messiah who died on a cross and later appeared to his followers as a resurrected being with flesh and bones.

The collision between the speculative world of Greek philosophy and the simple, literal faith and practice of the earliest Christians produced sharp contentions that threatened to widen political divisions in the fragmenting Roman empire. This led Emperor Constantine to convene the first churchwide council in a.d. 325. The action of this council of Nicaea remains the most important single event after the death of the Apostles in formulating the modern Christian concept of deity. The Nicene Creed erased the idea of the separate being of Father and Son by defining God the Son as being of “one substance with the Father.”

Other councils followed, and from their decisions and the writings of churchmen and philosophers there came a synthesis of Greek philosophy and Christian doctrine in which the orthodox Christians of that day lost the fulness of truth about the nature of God and the Godhead. The consequences persist in the various creeds of Christianity, which declare a Godhead of only one being and which describe that single being or God as “incomprehensible” and “without body, parts, or passions.” One of the distinguishing features of the doctrine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is its rejection of all of these postbiblical creeds (see Stephen E. Robinson, Are Mormons Christians? Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1991; Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, 4 vols., New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1992, s.v. “Apostasy,” “doctrine,” “God the Father,” and “Godhead”).

In the process of what we call the Apostasy, the tangible, personal God described in the Old and New Testaments was replaced by the abstract, incomprehensible deity defined by compromise with the speculative principles of Greek philosophy. The received language of the Bible remained, but the so-called “hidden meanings” of scriptural words were now explained in the vocabulary of a philosophy alien to their origins. In the language of that philosophy, God the Father ceased to be a Father in any but an allegorical sense. He ceased to exist as a comprehensible and compassionate being. And the separate identity of his Only Begotten Son was swallowed up in a philosophical abstraction that attempted to define a common substance and an incomprehensible relationship.

These descriptions of a religious philosophy are surely undiplomatic, but I hasten to add that Latter-day Saints do not apply such criticism to the men and women who profess these beliefs. We believe that most religious leaders and followers are sincere believers who love God and understand and serve him to the best of their abilities. We are indebted to the men and women who kept the light of faith and learning alive through the centuries to the present day. We have only to contrast the lesser light that exists among peoples unfamiliar with the names of God and Jesus Christ to realize the great contribution made by Christian teachers through the ages. We honor them as servants of God.

Then came the First Vision. An unschooled boy, seeking knowledge from the ultimate source, saw two personages of indescribable brightness and glory and heard one of them say, while pointing to the other, “This is My Beloved Son. Hear Him!” (JS—H 1:17.) The divine teaching in that vision began the restoration of the fulness of the gospel of Jesus Christ. God the Son told the boy prophet that all the “creeds” of the churches of that day “were an abomination in his sight” (JS—H 1:19). We affirm that this divine declaration was a condemnation of the creeds, not of the faithful seekers who believed in them. Joseph Smith’s first vision showed that the prevailing concepts of the nature of God and the Godhead were untrue and could not lead their adherents to the destiny God desired for them.

After a subsequent outpouring of modern scripture and revelation, this modern prophet declared, “The Father has a body of flesh and bones as tangible as man’s; the Son also; but the Holy Ghost has not a body of flesh and bones, but is a personage of Spirit” (D&C 130:22).

This belief does not mean that we claim sufficient spiritual maturity to comprehend God. Nor do we equate our imperfect mortal bodies to his immortal, glorified being. But we can comprehend the fundamentals he has revealed about himself and the other members of the Godhead. And that knowledge is essential to our understanding of the purpose of mortal life and of our eternal destiny as resurrected beings after mortal life.

In the theology of the restored church of Jesus Christ, the purpose of mortal life is to prepare us to realize our destiny as sons and daughters of God—to become like Him. Joseph Smith and Brigham Young both taught that “no man … can know himself unless he knows God, and he can not know God unless he knows himself” (in Journal of Discourses, 16:75; see also The Words of Joseph Smith, ed. Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, Provo: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980, p. 340). The Bible describes mortals as “the children of God” and as “heirs of God, and joint-heirs with Christ” (Rom. 8:16–17). It also declares that “we suffer with him, that we may be also glorified together” (Rom. 8:17) and that “when he shall appear, we shall be like him” (1 Jn. 3:2). We take these Bible teachings literally. We believe that the purpose of mortal life is to acquire a physical body and, through the atonement of Jesus Christ and by obedience to the laws and ordinances of the gospel, to qualify for the glorified, resurrected celestial state that is called exaltation or eternal life.

Like other Christians, we believe in a heaven or paradise and a hell following mortal life, but to us that two-part division of the righteous and the wicked is merely temporary, while the spirits of the dead await their resurrections and final judgments. The destinations that follow the final judgments are much more diverse. Our restored knowledge of the separateness of the three members of the Godhead provides a key to help us understand the diversities of resurrected glory.

In their final judgment, the children of God will be assigned to a kingdom of glory for which their obedience has qualified them. In his letters to the Corinthians, the Apostle Paul described these places. He told of a vision in which he was “caught up to the third heaven” and “heard unspeakable words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter” (2 Cor. 12:2, 4). Speaking of the resurrection of the dead, he described “celestial bodies,” “bodies terrestrial” (1 Cor. 15:40), and “bodies telestial” (JST, 1 Cor. 15:40), each pertaining to a different degree of glory. He likened these different glories to the sun, to the moon, and to different stars (see 1 Cor. 15:41).

We learn from modern revelation that these three different degrees of glory have a special relationship to the three different members of the Godhead.

The lowest degree is the telestial domain of those who “received not the gospel, neither the testimony of Jesus, neither the prophets” (D&C 76:101) and who have had to suffer for their wickedness. But even this degree has a glory that “surpasses all understanding” (D&C 76:89). Its occupants receive the Holy Spirit and the administering of angels, for even those who have been wicked will ultimately be “heirs of [this degree of] salvation” (D&C 76:88).

The next higher degree of glory, the terrestrial, “excels in all things the glory of the telestial, even in glory, and in power, and in might, and in dominion” (D&C 76:91). The terrestrial is the abode of those who were the “honorable men of the earth” (D&C 76:75). Its most distinguishing feature is that those who qualify for terrestrial glory “receive of the presence of the Son” (D&C 76:77). Concepts familiar to all Christians might liken this higher kingdom to heaven because it has the presence of the Son.

In contrast to traditional Christianity, we join with Paul in affirming the existence of a third or higher heaven. Modern revelation describes it as the celestial kingdom—the abode of those “whose bodies are celestial, whose glory is that of the sun, even the glory of God” (D&C 76:70). Those who qualify for this kingdom of glory “shall dwell in the presence of God and his Christ forever and ever” (D&C 76:62). Those who have met the highest requirements for this kingdom, including faithfulness to covenants made in a temple of God and marriage for eternity, will be exalted to the godlike state referred to as the “fulness” of the Father or eternal life (D&C 76:56, 94; see also D&C 131; D&C 132:19–20). (This destiny of eternal life or God’s life should be familiar to all who have studied the ancient Christian doctrine of and belief in deification or apotheosis.) For us, eternal life is not a mystical union with an incomprehensible spirit-god. Eternal life is family life with a loving Father in Heaven and with our progenitors and our posterity.

The theology of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ is comprehensive, universal, merciful, and true. Following the necessary experience of mortal life, all sons and daughters of God will ultimately be resurrected and go to a kingdom of glory. The righteous—regardless of current religious denomination or belief—will ultimately go to a kingdom of glory more wonderful than any of us can comprehend. Even the wicked, or almost all of them, will ultimately go to a marvelous—though lesser—kingdom of glory. All of that will occur because of God’s love for his children and because of the atonement and resurrection of Jesus Christ, “who glorifies the Father, and saves all the works of his hands” (D&C 76:43).

The purpose of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is to help all of the children of God understand their potential and achieve their highest destiny. This church exists to provide the sons and daughters of God with the means of entrance into and exaltation in the celestial kingdom. This is a family-centered church in doctrine and practices. Our understanding of the nature and purpose of God the Eternal Father explains our destiny and our relationship in his eternal family. Our theology begins with heavenly parents. Our highest aspiration is to be like them. Under the merciful plan of the Father, all of this is possible through the atonement of the Only Begotten of the Father, our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. As earthly parents we participate in the gospel plan by providing mortal bodies for the spirit children of God. The fulness of eternal salvation is a family matter.

It is the reality of these glorious possibilities that causes us to proclaim our message of restored Christianity to all people, even to good practicing Christians with other beliefs. This is why we build temples. This is the faith that gives us strength and joy to confront the challenges of mortal life. We offer these truths and opportunities to all people and testify to their truthfulness in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has many beliefs in common with other Christian churches. But we have differences, and those differences explain why we send missionaries to other Christians, why we build temples in addition to churches, and why our beliefs bring us such happiness and strength to deal with the challenges of life and death. I wish to speak about some of the important additions our doctrines make to the Christian faith. My subject is apostasy and restoration.

Last year searchers discovered a Roman fort and city in the Sinai close to the Suez Canal. Though once a major city, its location had been covered by desert sands and its existence had been forgotten for hundreds of years (see “Remains of Roman Fortress Emerge from Sinai Desert,” Deseret News, 6 Oct. 1994, p. A20). Discoveries like this contradict the common assumption that knowledge increases with the passage of time. In fact, on some matters the general knowledge of mankind regresses as some important truths are distorted or ignored and eventually forgotten. For example, the American Indians were in many respects more successful at living in harmony with nature than our modern society. Similarly, modern artists and craftsmen have been unable to recapture some of the superior techniques and materials of the past, like the varnish on a Stradivarius violin.

We would be wiser if we could restore the knowledge of some important things that have been distorted, ignored, or forgotten. This also applies to religious knowledge. It explains the need for the gospel restoration we proclaim.

When Joseph Smith was asked to explain the major tenets of our faith, he wrote what we now call the Articles of Faith. The first article states, “We believe in God, the Eternal Father, and in His Son, Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Ghost.” The Prophet later declared that “the simple and first principles of the gospel” include knowing “for a certainty the character of God” (“Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons, 15 Aug. 1844, p. 614). We must begin with the truth about God and our relationship to him. Everything else follows from that.

In common with the rest of Christianity, we believe in a Godhead of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. However, we testify that these three members of the Godhead are three separate and distinct beings. We also testify that God the Father is not just a spirit but is a glorified person with a tangible body, as is his resurrected Son, Jesus Christ.

When first communicated to mankind by prophets, the teachings we now have in the Bible were “plain and pure, and most precious and easy” to understand (1 Ne. 14:23). Even in the transmitted and translated version we have today, the Bible language confirms that God the Father and his resurrected Son, Jesus Christ, are tangible, separate beings. To cite only two of many such teachings, the Bible declares that man was created in the image of God, and it describes three separate members of the Godhead manifested at the baptism of Jesus (see Gen. 1:27; Matt. 3:13–17).

In contrast, many Christians reject the idea of a tangible, personal God and a Godhead of three separate beings. They believe that God is a spirit and that the Godhead is only one God. In our view, these concepts are evidence of the falling away we call the Great Apostasy.

We maintain that the concepts identified by such nonscriptural terms as “the incomprehensible mystery of God” and “the mystery of the Holy Trinity” are attributable to the ideas of Greek philosophy. These philosophical concepts transformed Christianity in the first few centuries following the deaths of the Apostles. For example, philosophers then maintained that physical matter was evil and that God was a spirit without feelings or passions. Persons of this persuasion, including learned men who became influential converts to Christianity, had a hard time accepting the simple teachings of early Christianity: an Only Begotten Son who said he was in the express image of his Father in Heaven and who taught his followers to be one as he and his Father were one, and a Messiah who died on a cross and later appeared to his followers as a resurrected being with flesh and bones.

The collision between the speculative world of Greek philosophy and the simple, literal faith and practice of the earliest Christians produced sharp contentions that threatened to widen political divisions in the fragmenting Roman empire. This led Emperor Constantine to convene the first churchwide council in a.d. 325. The action of this council of Nicaea remains the most important single event after the death of the Apostles in formulating the modern Christian concept of deity. The Nicene Creed erased the idea of the separate being of Father and Son by defining God the Son as being of “one substance with the Father.”

Other councils followed, and from their decisions and the writings of churchmen and philosophers there came a synthesis of Greek philosophy and Christian doctrine in which the orthodox Christians of that day lost the fulness of truth about the nature of God and the Godhead. The consequences persist in the various creeds of Christianity, which declare a Godhead of only one being and which describe that single being or God as “incomprehensible” and “without body, parts, or passions.” One of the distinguishing features of the doctrine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is its rejection of all of these postbiblical creeds (see Stephen E. Robinson, Are Mormons Christians? Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1991; Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, 4 vols., New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1992, s.v. “Apostasy,” “doctrine,” “God the Father,” and “Godhead”).

In the process of what we call the Apostasy, the tangible, personal God described in the Old and New Testaments was replaced by the abstract, incomprehensible deity defined by compromise with the speculative principles of Greek philosophy. The received language of the Bible remained, but the so-called “hidden meanings” of scriptural words were now explained in the vocabulary of a philosophy alien to their origins. In the language of that philosophy, God the Father ceased to be a Father in any but an allegorical sense. He ceased to exist as a comprehensible and compassionate being. And the separate identity of his Only Begotten Son was swallowed up in a philosophical abstraction that attempted to define a common substance and an incomprehensible relationship.

These descriptions of a religious philosophy are surely undiplomatic, but I hasten to add that Latter-day Saints do not apply such criticism to the men and women who profess these beliefs. We believe that most religious leaders and followers are sincere believers who love God and understand and serve him to the best of their abilities. We are indebted to the men and women who kept the light of faith and learning alive through the centuries to the present day. We have only to contrast the lesser light that exists among peoples unfamiliar with the names of God and Jesus Christ to realize the great contribution made by Christian teachers through the ages. We honor them as servants of God.

Then came the First Vision. An unschooled boy, seeking knowledge from the ultimate source, saw two personages of indescribable brightness and glory and heard one of them say, while pointing to the other, “This is My Beloved Son. Hear Him!” (JS—H 1:17.) The divine teaching in that vision began the restoration of the fulness of the gospel of Jesus Christ. God the Son told the boy prophet that all the “creeds” of the churches of that day “were an abomination in his sight” (JS—H 1:19). We affirm that this divine declaration was a condemnation of the creeds, not of the faithful seekers who believed in them. Joseph Smith’s first vision showed that the prevailing concepts of the nature of God and the Godhead were untrue and could not lead their adherents to the destiny God desired for them.

After a subsequent outpouring of modern scripture and revelation, this modern prophet declared, “The Father has a body of flesh and bones as tangible as man’s; the Son also; but the Holy Ghost has not a body of flesh and bones, but is a personage of Spirit” (D&C 130:22).

This belief does not mean that we claim sufficient spiritual maturity to comprehend God. Nor do we equate our imperfect mortal bodies to his immortal, glorified being. But we can comprehend the fundamentals he has revealed about himself and the other members of the Godhead. And that knowledge is essential to our understanding of the purpose of mortal life and of our eternal destiny as resurrected beings after mortal life.

In the theology of the restored church of Jesus Christ, the purpose of mortal life is to prepare us to realize our destiny as sons and daughters of God—to become like Him. Joseph Smith and Brigham Young both taught that “no man … can know himself unless he knows God, and he can not know God unless he knows himself” (in Journal of Discourses, 16:75; see also The Words of Joseph Smith, ed. Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, Provo: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980, p. 340). The Bible describes mortals as “the children of God” and as “heirs of God, and joint-heirs with Christ” (Rom. 8:16–17). It also declares that “we suffer with him, that we may be also glorified together” (Rom. 8:17) and that “when he shall appear, we shall be like him” (1 Jn. 3:2). We take these Bible teachings literally. We believe that the purpose of mortal life is to acquire a physical body and, through the atonement of Jesus Christ and by obedience to the laws and ordinances of the gospel, to qualify for the glorified, resurrected celestial state that is called exaltation or eternal life.

Like other Christians, we believe in a heaven or paradise and a hell following mortal life, but to us that two-part division of the righteous and the wicked is merely temporary, while the spirits of the dead await their resurrections and final judgments. The destinations that follow the final judgments are much more diverse. Our restored knowledge of the separateness of the three members of the Godhead provides a key to help us understand the diversities of resurrected glory.

In their final judgment, the children of God will be assigned to a kingdom of glory for which their obedience has qualified them. In his letters to the Corinthians, the Apostle Paul described these places. He told of a vision in which he was “caught up to the third heaven” and “heard unspeakable words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter” (2 Cor. 12:2, 4). Speaking of the resurrection of the dead, he described “celestial bodies,” “bodies terrestrial” (1 Cor. 15:40), and “bodies telestial” (JST, 1 Cor. 15:40), each pertaining to a different degree of glory. He likened these different glories to the sun, to the moon, and to different stars (see 1 Cor. 15:41).

We learn from modern revelation that these three different degrees of glory have a special relationship to the three different members of the Godhead.

The lowest degree is the telestial domain of those who “received not the gospel, neither the testimony of Jesus, neither the prophets” (D&C 76:101) and who have had to suffer for their wickedness. But even this degree has a glory that “surpasses all understanding” (D&C 76:89). Its occupants receive the Holy Spirit and the administering of angels, for even those who have been wicked will ultimately be “heirs of [this degree of] salvation” (D&C 76:88).

The next higher degree of glory, the terrestrial, “excels in all things the glory of the telestial, even in glory, and in power, and in might, and in dominion” (D&C 76:91). The terrestrial is the abode of those who were the “honorable men of the earth” (D&C 76:75). Its most distinguishing feature is that those who qualify for terrestrial glory “receive of the presence of the Son” (D&C 76:77). Concepts familiar to all Christians might liken this higher kingdom to heaven because it has the presence of the Son.

In contrast to traditional Christianity, we join with Paul in affirming the existence of a third or higher heaven. Modern revelation describes it as the celestial kingdom—the abode of those “whose bodies are celestial, whose glory is that of the sun, even the glory of God” (D&C 76:70). Those who qualify for this kingdom of glory “shall dwell in the presence of God and his Christ forever and ever” (D&C 76:62). Those who have met the highest requirements for this kingdom, including faithfulness to covenants made in a temple of God and marriage for eternity, will be exalted to the godlike state referred to as the “fulness” of the Father or eternal life (D&C 76:56, 94; see also D&C 131; D&C 132:19–20). (This destiny of eternal life or God’s life should be familiar to all who have studied the ancient Christian doctrine of and belief in deification or apotheosis.) For us, eternal life is not a mystical union with an incomprehensible spirit-god. Eternal life is family life with a loving Father in Heaven and with our progenitors and our posterity.

The theology of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ is comprehensive, universal, merciful, and true. Following the necessary experience of mortal life, all sons and daughters of God will ultimately be resurrected and go to a kingdom of glory. The righteous—regardless of current religious denomination or belief—will ultimately go to a kingdom of glory more wonderful than any of us can comprehend. Even the wicked, or almost all of them, will ultimately go to a marvelous—though lesser—kingdom of glory. All of that will occur because of God’s love for his children and because of the atonement and resurrection of Jesus Christ, “who glorifies the Father, and saves all the works of his hands” (D&C 76:43).

The purpose of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is to help all of the children of God understand their potential and achieve their highest destiny. This church exists to provide the sons and daughters of God with the means of entrance into and exaltation in the celestial kingdom. This is a family-centered church in doctrine and practices. Our understanding of the nature and purpose of God the Eternal Father explains our destiny and our relationship in his eternal family. Our theology begins with heavenly parents. Our highest aspiration is to be like them. Under the merciful plan of the Father, all of this is possible through the atonement of the Only Begotten of the Father, our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. As earthly parents we participate in the gospel plan by providing mortal bodies for the spirit children of God. The fulness of eternal salvation is a family matter.

It is the reality of these glorious possibilities that causes us to proclaim our message of restored Christianity to all people, even to good practicing Christians with other beliefs. This is why we build temples. This is the faith that gives us strength and joy to confront the challenges of mortal life. We offer these truths and opportunities to all people and testify to their truthfulness in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Friday, October 10, 2008

Seventeen Centuries of Christianity

De Lamar Jensen, “Seventeen Centuries of Christianity,” Ensign, Sep 1978, 51

The story of Christianity is not simple to tell or easy to comprehend.

It contains cruelty as well as kindness, tragedy as well as triumph. It is the story of human endeavor to pursue a divine purpose without fully understanding what that purpose is: having a form of godliness, but denying the power thereof. (JS—H 1:19.) Many church leaders over the centuries were miscreants of the worst kind, sowing seeds of confusion and corruption in the church.

But many others were worthy people who paid attention to the “still small voice,” who understood at least in part the teachings of the Savior, and who promoted love, goodness, and obedience to God’s commandments. These are the ones who responded to the light they had received and helped prepare for the day when God would restore the priesthood and gospel in its fulness.

The Primitive Church

The primitive church of Christ, composed both of loyal Jews who had heard the message of the Savior and many gentiles converted to Christianity through the missionary labors of Paul and others, spread quickly around the perimeter of the eastern Mediterranean.

By the time of John’s exile to the Isle of Patmos, Christian communities existed in Syria and Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, North Africa, Greece, Macedonia, and Italy. The instructions of Jesus to his apostles to go forth and teach all nations were followed faithfully. The people of God no longer belonged to a single nation but to a universal church.

Expansion continued during the next century, and congregations of Christians were dispersed as far eastward as Arbela in Persia, and westward to Vienne and Lyon in Gaul (modern France). Obviously, the political, linguistic, and cultural diversity of these communities was enormous, and the problem of communication overwhelming. Yet they all had two things in common: a testimony of the resurrected Christ, and the perennial threat of persecution.

For three hundred years Christians were scorned and persecuted, first in Jerusalem by their Jewish countrymen and later by official proscription throughout the Roman Empire. Free exercise of the Jewish religion was permitted under Roman rule, and as long as Christians were considered as part of Judaism they were unmolested by Roman authorities. But it soon became evident, from their rejection by the Jews and the rapid influx of gentiles into their fold, that the followers of Christ were not included among the followers of the Mosaic law.

Christians’ refusal to worship and sacrifice to the Roman emperor condemned their faith to the status of an illicit religion under Roman law. Official state persecution began with Nero in the first century a.d. and was sporadically renewed and intensified under subsequent emperors. Besides physical persecution, Christians were also subjected to extreme social discrimination and continuous suspicion and hatred.

Despite all of these oppressions, Christianity continued to grow in strength and number. As it did, it encountered more pernicious threats from the infiltration of Eastern mystery cults and religious philosophies that seeped into Christianity during the second and third centuries a.d. Christians fought these influences, but similarities between them and Christian beliefs made it difficult at times to distinguish between the philosophies.

Had the people been able to seek the counsel and inspiration of prophetic leaders they might yet have maintained a constant course. But with the death of the apostles, general priesthood leadership was lost, and with it the vision of divine direction and purpose. Members and local leaders were left to their own resources to solve their mounting problems, although the channel of communication with God remained open for anyone who was worthy and willing to use it.

Alteration and Dissent

The original organization of apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, teachers, elders, bishops, and deacons underwent gradual change as situations and personnel altered and as people’s views and customs varied. Likewise, doctrines grew more diverse as conflicting opinions arose over the content and meaning of Christ’s teachings.

To arrest such tendencies, Christians tried to establish norms of belief and behavior. They began the search for authentic documents from the time of Jesus and the apostles to serve as guides. Even then disagreements arose as to the authenticity and propriety of many of the sources uncovered, and some were never found at all.

By the close of the second century, however, agreement was fairly widespread that the four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, along with a number of Paul’s epistles and some from James, Peter, and John, should be recognized as the New Testament. In 367 a.d. the present collection of twenty-seven books was accepted.

Another attempt to conserve the faith appeared in the so-called Apostles’ Creed, a concise statement of doctrinal belief in God the Father and his Son, Jesus Christ, intended specifically to repudiate some of the tenets of Marcionism, another Eastern religion with similarities to Christianity.

In the meantime, several individuals rose to defend the faith against heretical influences. In so doing they introduced such philosophical subtleties and hair-splitting definitions that it became difficult for ordinary Christians to comprehend even basic beliefs. Among these well-meaning but misleading early church fathers was Tertullian of Carthage (Circa 150–220 a.d.), a learned lawyer whose definition of the Trinity as three in person but one in substance initiated the Christian confusion over the Godhead. Others included Clement of Alexandria (Circa 150–215 a.d.), who employed Greek philosophy to describe the nature of Christ (the Logos, or Word, always existed as the “face” of God); and Clement’s prize pupil, Origen (Circa 185–254 a.d.), a pious and brilliant teacher who held that Christ is the Logos in flesh, coeternal with but subordinate to the Father and associated in dignity with the uncreated Holy Ghost.

Dissension continued, particularly concerning Christ’s nature and his relationship to the Father, until these controversies led to a major schism among Christians. Arius (Circa 250–336), a priest in the church of Alexandria, believed and taught that although God is without beginning or end, the Son had a beginning and is therefore neither God nor man, being a creation of God. Arius’s views spread rapidly into the eastern part of the empire where violent controversy quickly followed.

Emperor Constantine, who had converted to Christianity in 312 a.d. and lifted the imperial ban against Christians, feared that the Arian controversy might divide the empire he had so recently united. He convened the first general council of the church in Nicaea, near Constantinople, in 325 a.d. The council did not end doctrinal strife, but it did condemn Arianism and issued the Nicene Creed, which declared universal belief in “one God, the Father Almighty, … and in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the only-begotten of the Father, that is, of the substance of the Father, … begotten, not made, of one substance with the Father.” Despite this pronouncement, the controversy continued to plague the church as the Nicene Creed was alternately accepted and rejected by subsequent emperors.

These myopic gropings emphasize the futility of comprehending spiritual matters without the gift of the Spirit. They also underline the doctrinal and regional fragmentation of the church during the decay and breakup of the Western Roman Empire between 300 and 600 a.d. By 787 a.d., no fewer than seven councils had convened to try to solve the theological arguments.

The Latin Fathers

The theology of the Western portion of Christendom was strongly influenced by four men of the fourth and early fifth centuries: Ambrose, Jerome, John Chrysostom, and Augustine, known collectively as the Latin Fathers.

As bishop of Milan, Ambrose (Circa 340–397) struggled to proclaim and maintain the independence of the church from the encroachments of the state.

Jerome (Circa 345–420) is remembered as the scholarly ascetic who translated the Bible into the Latin version (the Vulgate) that is still used by the Roman Catholic Church.

After years as a monk, John Chrysostom (347–Circa 407) became the most eloquent preacher in the early church (Chrysostom meaning “golden mouth”).

Augustine (354–430), bishop of Hippo in North Africa, wrote several works: The Confessions, revealing his own life in the light of God’s grace; The City of God, setting forth his philosophy of history as the dichotomy between the kingdom of man and the kingdom of God; and On the Trinity, giving final form to the Western church’s teaching of the divine Trinity. Heavily influenced by paganism, Augustine expounded a view of man and God that was hardly complimentary to either.

Conquest and Conversion

For five hundred years after the death of Augustine the Western church was ravaged and desolated by the decay of the protective Roman Empire, by the ensuing invasions from the north (Goths, Vandals, Saxons, Franks, and Vikings), and by the conquests of a vigorous new religion from the Middle East—Islam. Carried throughout Arabia, Mesopotamia, Persia, Syria, Palestine, North Africa, and into Europe through the Iberian peninsula, Islam spread until, by the middle of the eighth century, half of Christendom had come under Islamic rule. Christianity survived, however, though weakened and reduced, and began the slow process of recovering its losses and conquering the conquerors. Step by step, the barbarian invaders were converted to Christianity: the Franks first, then the Anglo-Saxons, the Frisians, and the other Germans. Goths, Lombards, and Burgundians were assimilated into Latin Christendom, as were the vagrant Norsemen. By the end of the eleventh century, Christian crusaders were returning to the East to “redeem” the Holy Land.

A Professional Clergy

Perhaps the most significant change during those “dark ages” was the complete split between the Eastern and Western churches, and the rise of a professional, hierarchical clergy in the West, culminating in the powerful papacy.

The growth of papal power was slow but inexorable. In Constantine’s time, the bishop of Rome was only one of many bishops, with no more authority in the church as a whole than the bishops of Alexandria, Antioch, or Constantinople. But by the thirteenth century, as pope, he boldly proclaimed his supremacy over all the world and its kingdoms.

Constantine and each of his immediate successors had been head of the church—making it an imperial theocracy that continued in the East until 1453. The bishops of Rome, however, contested the imperial supremacy and pronounced their own “primacy” on the ground that Rome was the “Apostolic See,” the center established by the apostle Peter.

In the fifth century Roman bishops began using the title pope (father) to emphasize their superiority to other bishops, a position strongly asserted by Leo I “The Great” (440–61) and expanded by several strong-willed successors. By the middle of the eighth century, when Pope Stephen II sought and received the protection of the Frankish king, the papacy had fully freed itself from imperial authority and resumed its climb to Europeanwide power.

The medieval church was governed by an intricate hierarchical system consisting of the pope at the top, archbishops and bishops in the middle, and parish priests at the bottom. In addition to their jurisdictional functions, priests administered seven sacraments (baptism, confirmation, marriage, ordination, penance, eucharist, and extreme unction). These sacraments were believed to be the channels by which divine grace was imparted to man.

Religious Orders

Separate from these ecclesiastical officers was another group who provided educational and social services and encouraged certain ascetic and personal expressions of Christian piety. These were the orders of monks and nuns, whose lives were regulated by their respective orders, and who took upon themselves formal vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

Medieval monasticism had evolved through a long history, beginning in the third century with early hermits like St. Anthony, who took literally Christ’s injunction to the rich young man to “go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor.” (Matt. 19:21.) Later monks lived communally in monasteries under strict rules, attempting to live in the world but not be of it.

Another kind of religious order, the mendicant friars, came into being in the thirteenth century. Rather than secluding themselves in monasteries, they sought to carry the Christian message by teaching and good deeds.

The first of these orders was the Franciscan, or Friars Minor, founded in Italy by St. Francis of Assisi (1182–1226). Francis’s own life was one of simple and sensitive devotion to God and unselfish service to mankind. A kind-hearted and gentle man, he urged others to love God and neighbors, to forgive freely, and to abstain from all vices of the flesh.

The Dominican Order, or Friars Preachers, was founded by a Spanish priest and student, St. Dominic (Dominic de Guzman, 1170–1221). The mission of this order was to preach to the weak in spirit, to convert the non-Christians, and to teach repentance to the wayward.

Reaction against the Clergy

Many wayward souls did respond to Dominic’s efforts, but others believed the church possessed neither the true gospel nor the authority of God. Such a religious group was the Cathari (“pure ones”) of southern France (known also as Albigenses, after the city of Albi which was their center).

The Cathari, like the earlier Manichaeans, believed the material world was evil and only the spiritual realm was good. They accepted the New Testament (being from God), but they rejected the Old Testament (inspired by Jehovah, creator of the wicked world) along with many teachings and interpretations of the Roman church, including the sacraments. They sharply criticized the growing wealth and power of the clergy. Politics and economic jealousies soon entered the picture until a full-scale crusade was launched against them in 1209.

Another movement branded as heretical was the Waldenses, followers of Peter Waldo (Valdez) of Lyon. The Waldenses, like the Cathari, also spread across southeastern France, northern Spain, northern Italy, and southern Germany. They went in simple garb, two by two without purse or script, teaching their version or the gospel to all who would listen. Forbidding oaths and rejecting masses and prayers for the dead, they soon came under condemnation, and like the Cathari (with whom they disagreed), they suffered persecution and death.

The presence of these and other heresies in the medieval church gave added incentive to the development of “scholastic” arguments for refuting doctrinal error and unbelief. Scholasticism developed in conjunction with the rise of the universities and provided a broad philosophical base for the verification of church dogmas.

This introduction of reason and logic into Christian theology, to serve as an adjunct rather than an enemy to faith, was one of the triumphs of medieval thought. The greatest of the schoolmen was Thomas Aquinas (1225–74), a Dominican teacher whose Summa Theologica, a masterpiece of scholastic reasoning making great use of Aristotelian logic, overcame the apparent conflicts between natural and revealed thought and provided logical proofs of Christian doctrines for the people of the time.

Corruption and Disillusionment

But logic was no more effective than the sword in maintaining religious unity when the leadership of the church itself was steeped in error and engrossed in sin. Of course, not all of the clergy were unworthy. Many priests and monks were sincere, hard-working, and honest; but too many of them were not. By the fourteenth century clerical corruption and abuse were widespread. Absenteeism, venality, concubinage, and slothfulness were common among prelates at every level.

Unfortunately, involved as it was with “high politics,” competing with the secular rulers, the papacy did little to retard this process of deterioration. When Pope Boniface VIII issued the bull (or edict) Unam Sanctum in 1302, which reiterated the papal claim to universal supremacy, he not only infuriated the French king but also alienated many others. Consequently, the Roman see was abolished and the papacy was transplanted to Avignon, in France, where the King could keep a close watch on it. Seventy years later the Great Schism began—a succession of rival popes at Avignon and Rome each denouncing and excommunicating the other, while corruption and confusion ran rampant.

Meanwhile, most honest believers were bewildered and disillusioned. The church was an integral part of their lives and promised the only recognizable path to their salvation. Yet in many ways it was a remote, even hostile, stranger to them.

In a very real sense there were three Catholic churches, and only one of these touched the lives of people in a meaningful way. There was the church of the upper clergy (especially the bishops and cardinals), vying for influence and prestige in a world of power and violence. There was the church of the scholastics and monks, where doctrines were more highly esteemed than morals. And there was the devotional church of the fifty million lay members whose contact with religion came through the mass and other sacraments, and through pilgrimages, prayers, rosaries, relics, and intercessional appeals to the Virgin Mary and to early saints.

Reforms

During the Renaissance (from about 1350–1550), pressures mounted to reform the church and reduce its abuses. This was not the first genuine attempt at reformation. In the tenth century, a revitalization of the monastic system was triggered at the monastery of Cluny, north of Lyon. The cluniac reforms, stressing service, obedience, and piety, had a wide effect which was renewed two hundred years later by Bernard of Clairvaux and the Cistercians.

Even the papacy felt these fresh winds of reform under the indomitable Hildrebrand (Pope Gregory VII, 1073–85), but it did not last. Frequently during the next four centuries pious and well-meaning clergy tried to eliminate abuses within their own jurisdictions, but the problems were usually too interrelated to be successfully attacked piecemeal. Churchwide action was needed but was not forthcoming.

Many people turned to mysticism both for personal catharsis and for churchwide spiritualization. Some formed into societies, such as the Friends of God in the Rhineland and the Brethren of the Common Life in the Netherlands. From one of these groups came the most influential devotional book of the Renaissance, Thomas a Kempis’ Imitation of Christ.

Some of these mystics were sainted (St. Bridget of Sweden, St. Catherine of Siena, San Bernardino of Siena, and San Giovanni Capistrano), while others were charged with heresy. John Wyclif of Oxford and John Hus of Prague were among the latter.

During the final years of the Great Schism (1378–1415), as the divided papacy continued to degenerate, the cry was increasingly heard to convene a general council of the church. This movement gained momentum until it boldly asserted that the supreme governing body of the church was not the pope but a general council representing all Christendom.

The Council of Constance thus convened in 1414. During the next three years it deposed all three rival popes; chose a new one of its own (intended to be a figurehead); charged, heard, condemned, and then brutally killed John Hus; and hesitatingly approached the task of reforming the church “in head and members.”

Yet it did not accomplish its goals. A newly established Renaissance papacy quickly regained its position of primacy. The execution of Hus, instead of ending heresy, caused the Hussites to take up arms for the next half century, devastating much of central and eastern Europe. For the council, reform of the church soon became a dead issue.

It was not a dead issue, however, for all those who saw and were offended by the continuing corruption. Among the more outspoken of these were the Renaissance humanists, men whose devotion to the church was not compromised by their open criticism of its abuses.

Humanism was mainly a scholarly and literary movement whose admiration of classical languages and culture made it suspect in the eyes of many churchmen. The humanists were critical of scholasticism because of its irrelevance, and were vigorously opposed to the immoral lives of the clergy. “What point is there in your being showered with holy water if you do not wipe away the inward pollution from your heart?” chided Erasmus, the greatest of the humanists. “You venerate the saints and delight in touching their relics, but you despise the best one they left behind, the example of a holy life.”

Sir Thomas More echoed that sentiment in his Utopia and in other writings. The humanists held a more optimistic view of human nature and the dignity of man than did the theologians, and placed more trust in the words of scripture than in the subsequent commentaries of the scholastics. Yet they did not wish to harm the church nor divide it; they hoped to unite and strengthen it. To do that, they advocated study, prayer, and a thorough reformation of the lives of the clergy.

Protestantism

One of the clergy, an Augustinian monk and doctor of theology named Martin Luther, was less disturbed by the profusion of immoral conduct (although he condemned that too) than by what he called “the deliberate silence regarding the world of Truth, or else its adulteration.”

In a desperate endeavor to attain salvation through the conscientious performance of meritorious works prescribed by the church, Luther concluded that no man can merit salvation, that it is a gift of God given freely to whom he wills, not as a reward for good deeds but according to divine pleasure. By this simple pronouncement, Luther launched the Protestant Reformation and began the process that would lead first to a split and then a complete fragmentation of Christianity.

If mankind does not need works, indulgences, or sacraments for salvation, he reasoned, then the entire hierarchical system of the Roman church is superfluous and perverse. Indeed, he declared, the pope is not only a hoax, he is the very anti-Christ! Leaning heavily on Augustine’s definition of “original sin,” which declared all mankind to be wicked, depraved, lustful, and an enemy to God, Luther expounded the idea of salvation by grace alone (sola gratia), whereby God chooses some, regardless of their works, to repentance, faith, and salvation through Jesus Christ. Thus redeemed from their own wickedness, the “true believers”—the invisible church of Christ—become righteous doers of good for the right reasons.

Lutheranism spread into many states of Germany and beyond into Scandinavia and eastern Europe. Others quickly took up the Bible to proclaim similar views. Luther believed that no matter how many people read the scriptures, they would all reach the same conclusion if they used good reason and followed their conscience.

But, alas, it was not so. Some groups refuted clerical and monastic vows, others destroyed images, while still others, such as the “Zwichau prophets,” declared the immediate advent of the Lord.

In Switzerland, Ulrich Zwingli renounced the tithe, repudiated clerical celibacy, and abolished the mass. In England Henry VIII rejected the pope and declared himself “the only supreme head in earth of the Church of England.”

John Calvin, a lawyer-theologian from France, carried Protestant doctrines to their logical extreme in his Institutes of the Christian Religion, unabashedly pronouncing the predestination of the elect to salvation and the rest to damnation. At Geneva he established a tightly organized theocracy from which ardent pastors and teachers carried Calvinism into France, the Netherlands, England, Scotland, Germany, Bohemia, and Poland, thus providing the principal theological base of Puritanism, Presbyterianism, Congregationalism, and Dutch, French, and German Reformed faiths.

From the eddies of this Protestant upheaval other groups of reformers emerged. Some of these were called Anabaptists (rebaptizers) because they rejected the practice of infant baptism practiced by both Catholics and Protestants and proclaimed instead baptism by immersion, following conversion and repentance, as a sign of entrance into God’s kingdom.

They usually referred to themselves as “brethren,” or “saints.” Because they came largely from the lower classes, believed in a complete separation of church and state (including refusal to take civil oaths, bear arms, or pay taxes), and had extreme beliefs about the end of the world, they are frequently spoken of as the Radical Reformers. But for the most part they were peaceful and devout followers of Christ.

They believed in a restitution of the primitive church with its organization and communal life. They had no paid ministry, believed that every believer received divine help in understanding the word of God, and rejected the Protestant doctrine of salvation by grace alone, teaching instead salvation by faith and works.

Because they were so different, and their theory of church and state considered dangerous to society, they were feared and ruthlessly persecuted by Catholic and Protestant alike. Most of those who survived did so by fleeing to the east where, under the looser jurisdiction of the rulers of Moravia and Poland, they retained their unique identity and devotion.

Obviously, the Protestant Reformation did not reform the church; it fractured and divided it. Christendom was hopelessly fragmented by the middle of the sixteenth century. Recrimination, persecution, and bloodshed followed. Sincere Catholic reformers—men like Bishop Matteo Giberti and Cardinal Gasparo Contarini—could not prevent the Counter Reformation from over-reacting to the Protestant threat. The Inquisition was revived in a vain effort to wipe out heresy.

Even Ignatius Loyola’s new religious order, the Jesuits, founded in 1540 to teach the young and convert the heathen, was soon turned into an instrument for fighting Protestantism. The council of Trent (which ended in 1563) hardened the lines of religious division, and the Papal Index of Prohibited Books further constricted Christian thought. In a few years the spread of Protestantism was checked, but at an enormous cost.

Still the proliferation of new faiths within Protestantism continued. The rigors of Calvinism in the Netherlands soon generated a reaction there in the form of Arminianism, which tried to moderate the harshness of absolute predestination and “irresistible grace” with a more liberal interpretation of God’s foreknowledge and man’s free will.

In Germany, after the Thirty Years War (1618–48) had taken its gruesome toll, a movement known as Pietism deepened the spiritual life of many Lutherans by cultivating high moral standards and promoting organized works of charity and service.

And in England, George Fox (1624–91) founded the remarkable Society of Friends, known popularly as the Quakers, resembling the earlier Anabaptists in many ways: spiritual revelation, non-professional ministry, rejection of oaths, titles, and war. True Christians, they felt, will be known by their fruits—a consecrated, simple, spiritual life.

While all of these movements met with immediate distrust, anger, and violence, eventually even the fanaticism of religious war subsided and in the pluralism of post-Reformation Europe religious toleration began slowly to appear.

The Enlightenment

That progress toward toleration was aided in the eighteenth century by the spirit of the Enlightenment, particularly the rise of rationalism and “natural religion” (or Deism). According to Deist views, God exists; he created the world, which is then governed by its own natural laws. God should be respected and praised, and men should repent of their sins and do good to one another. The emphasis throughout was on virtue and conduct instead of theology. How foolish it is, noted Voltaire, the most famous of the French Deists, for men to torture and kill one another over the definition of a word or the phrasing of a creed,

Reason and morality were the watchwords of “Enlightened” society. Yet something essential to Christianity was missing in this rational religion: the intimacy of God and the divinity of Christ. Christianity without the miracles of the birth, Resurrection, and Atonement is not Christianity at all. The new humanitarianism can only be praised—for too long it had been ignored by partisan theologians—but the Deist rejection of theology, although making room for greater toleration of different Christian sects, was a criticism of Christianity itself.

Partly in response to the Deist influence came a wide-ranging evangelical awakening, especially in England. It stressed the fundamentals of Christian devotion and particularly the renewal and revitalization of life which results from a full commitment to Christ.

A notable product of this evangelicalism was a new society called Methodism, whose chief architects were John (1703–91) and Charles (1707–77) Wesley. Methodist emphasis upon “conversion” and cultivation of the Christian life, including service to others, contributed materially to a revival of Christianity and to the active promotion of social reforms, such as the abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807.

And thus for seventeen centuries Christianity struggled through trials of every kind, from persecution to prosperity, from harmony to discord and disintegration, groping for answers to questions asked and unasked. As its proponents ignored or misunderstood the teachings of Christ and his apostles, Christianity foundered. As they responded to glimmers of that original light, Christianity during these centuries helped prepare men and nations for the fulness of the restored gospel.

The story of Christianity is not simple to tell or easy to comprehend.

It contains cruelty as well as kindness, tragedy as well as triumph. It is the story of human endeavor to pursue a divine purpose without fully understanding what that purpose is: having a form of godliness, but denying the power thereof. (JS—H 1:19.) Many church leaders over the centuries were miscreants of the worst kind, sowing seeds of confusion and corruption in the church.

But many others were worthy people who paid attention to the “still small voice,” who understood at least in part the teachings of the Savior, and who promoted love, goodness, and obedience to God’s commandments. These are the ones who responded to the light they had received and helped prepare for the day when God would restore the priesthood and gospel in its fulness.

The Primitive Church

The primitive church of Christ, composed both of loyal Jews who had heard the message of the Savior and many gentiles converted to Christianity through the missionary labors of Paul and others, spread quickly around the perimeter of the eastern Mediterranean.

By the time of John’s exile to the Isle of Patmos, Christian communities existed in Syria and Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, North Africa, Greece, Macedonia, and Italy. The instructions of Jesus to his apostles to go forth and teach all nations were followed faithfully. The people of God no longer belonged to a single nation but to a universal church.

Expansion continued during the next century, and congregations of Christians were dispersed as far eastward as Arbela in Persia, and westward to Vienne and Lyon in Gaul (modern France). Obviously, the political, linguistic, and cultural diversity of these communities was enormous, and the problem of communication overwhelming. Yet they all had two things in common: a testimony of the resurrected Christ, and the perennial threat of persecution.

For three hundred years Christians were scorned and persecuted, first in Jerusalem by their Jewish countrymen and later by official proscription throughout the Roman Empire. Free exercise of the Jewish religion was permitted under Roman rule, and as long as Christians were considered as part of Judaism they were unmolested by Roman authorities. But it soon became evident, from their rejection by the Jews and the rapid influx of gentiles into their fold, that the followers of Christ were not included among the followers of the Mosaic law.

Christians’ refusal to worship and sacrifice to the Roman emperor condemned their faith to the status of an illicit religion under Roman law. Official state persecution began with Nero in the first century a.d. and was sporadically renewed and intensified under subsequent emperors. Besides physical persecution, Christians were also subjected to extreme social discrimination and continuous suspicion and hatred.

Despite all of these oppressions, Christianity continued to grow in strength and number. As it did, it encountered more pernicious threats from the infiltration of Eastern mystery cults and religious philosophies that seeped into Christianity during the second and third centuries a.d. Christians fought these influences, but similarities between them and Christian beliefs made it difficult at times to distinguish between the philosophies.

Had the people been able to seek the counsel and inspiration of prophetic leaders they might yet have maintained a constant course. But with the death of the apostles, general priesthood leadership was lost, and with it the vision of divine direction and purpose. Members and local leaders were left to their own resources to solve their mounting problems, although the channel of communication with God remained open for anyone who was worthy and willing to use it.

Alteration and Dissent

The original organization of apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, teachers, elders, bishops, and deacons underwent gradual change as situations and personnel altered and as people’s views and customs varied. Likewise, doctrines grew more diverse as conflicting opinions arose over the content and meaning of Christ’s teachings.

To arrest such tendencies, Christians tried to establish norms of belief and behavior. They began the search for authentic documents from the time of Jesus and the apostles to serve as guides. Even then disagreements arose as to the authenticity and propriety of many of the sources uncovered, and some were never found at all.