De Lamar Jensen, “Seventeen Centuries of Christianity,” Ensign, Sep 1978, 51

The story of Christianity is not simple to tell or easy to comprehend.

It contains cruelty as well as kindness, tragedy as well as triumph. It is the story of human endeavor to pursue a divine purpose without fully understanding what that purpose is: having a form of godliness, but denying the power thereof. (JS—H 1:19.) Many church leaders over the centuries were miscreants of the worst kind, sowing seeds of confusion and corruption in the church.

But many others were worthy people who paid attention to the “still small voice,” who understood at least in part the teachings of the Savior, and who promoted love, goodness, and obedience to God’s commandments. These are the ones who responded to the light they had received and helped prepare for the day when God would restore the priesthood and gospel in its fulness.

The Primitive Church

The primitive church of Christ, composed both of loyal Jews who had heard the message of the Savior and many gentiles converted to Christianity through the missionary labors of Paul and others, spread quickly around the perimeter of the eastern Mediterranean.

By the time of John’s exile to the Isle of Patmos, Christian communities existed in Syria and Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, North Africa, Greece, Macedonia, and Italy. The instructions of Jesus to his apostles to go forth and teach all nations were followed faithfully. The people of God no longer belonged to a single nation but to a universal church.

Expansion continued during the next century, and congregations of Christians were dispersed as far eastward as Arbela in Persia, and westward to Vienne and Lyon in Gaul (modern France). Obviously, the political, linguistic, and cultural diversity of these communities was enormous, and the problem of communication overwhelming. Yet they all had two things in common: a testimony of the resurrected Christ, and the perennial threat of persecution.

For three hundred years Christians were scorned and persecuted, first in Jerusalem by their Jewish countrymen and later by official proscription throughout the Roman Empire. Free exercise of the Jewish religion was permitted under Roman rule, and as long as Christians were considered as part of Judaism they were unmolested by Roman authorities. But it soon became evident, from their rejection by the Jews and the rapid influx of gentiles into their fold, that the followers of Christ were not included among the followers of the Mosaic law.

Christians’ refusal to worship and sacrifice to the Roman emperor condemned their faith to the status of an illicit religion under Roman law. Official state persecution began with Nero in the first century a.d. and was sporadically renewed and intensified under subsequent emperors. Besides physical persecution, Christians were also subjected to extreme social discrimination and continuous suspicion and hatred.

Despite all of these oppressions, Christianity continued to grow in strength and number. As it did, it encountered more pernicious threats from the infiltration of Eastern mystery cults and religious philosophies that seeped into Christianity during the second and third centuries a.d. Christians fought these influences, but similarities between them and Christian beliefs made it difficult at times to distinguish between the philosophies.

Had the people been able to seek the counsel and inspiration of prophetic leaders they might yet have maintained a constant course. But with the death of the apostles, general priesthood leadership was lost, and with it the vision of divine direction and purpose. Members and local leaders were left to their own resources to solve their mounting problems, although the channel of communication with God remained open for anyone who was worthy and willing to use it.

Alteration and Dissent

The original organization of apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, teachers, elders, bishops, and deacons underwent gradual change as situations and personnel altered and as people’s views and customs varied. Likewise, doctrines grew more diverse as conflicting opinions arose over the content and meaning of Christ’s teachings.

To arrest such tendencies, Christians tried to establish norms of belief and behavior. They began the search for authentic documents from the time of Jesus and the apostles to serve as guides. Even then disagreements arose as to the authenticity and propriety of many of the sources uncovered, and some were never found at all.

By the close of the second century, however, agreement was fairly widespread that the four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, along with a number of Paul’s epistles and some from James, Peter, and John, should be recognized as the New Testament. In 367 a.d. the present collection of twenty-seven books was accepted.

Another attempt to conserve the faith appeared in the so-called Apostles’ Creed, a concise statement of doctrinal belief in God the Father and his Son, Jesus Christ, intended specifically to repudiate some of the tenets of Marcionism, another Eastern religion with similarities to Christianity.

In the meantime, several individuals rose to defend the faith against heretical influences. In so doing they introduced such philosophical subtleties and hair-splitting definitions that it became difficult for ordinary Christians to comprehend even basic beliefs. Among these well-meaning but misleading early church fathers was Tertullian of Carthage (Circa 150–220 a.d.), a learned lawyer whose definition of the Trinity as three in person but one in substance initiated the Christian confusion over the Godhead. Others included Clement of Alexandria (Circa 150–215 a.d.), who employed Greek philosophy to describe the nature of Christ (the Logos, or Word, always existed as the “face” of God); and Clement’s prize pupil, Origen (Circa 185–254 a.d.), a pious and brilliant teacher who held that Christ is the Logos in flesh, coeternal with but subordinate to the Father and associated in dignity with the uncreated Holy Ghost.

Dissension continued, particularly concerning Christ’s nature and his relationship to the Father, until these controversies led to a major schism among Christians. Arius (Circa 250–336), a priest in the church of Alexandria, believed and taught that although God is without beginning or end, the Son had a beginning and is therefore neither God nor man, being a creation of God. Arius’s views spread rapidly into the eastern part of the empire where violent controversy quickly followed.

Emperor Constantine, who had converted to Christianity in 312 a.d. and lifted the imperial ban against Christians, feared that the Arian controversy might divide the empire he had so recently united. He convened the first general council of the church in Nicaea, near Constantinople, in 325 a.d. The council did not end doctrinal strife, but it did condemn Arianism and issued the Nicene Creed, which declared universal belief in “one God, the Father Almighty, … and in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the only-begotten of the Father, that is, of the substance of the Father, … begotten, not made, of one substance with the Father.” Despite this pronouncement, the controversy continued to plague the church as the Nicene Creed was alternately accepted and rejected by subsequent emperors.

These myopic gropings emphasize the futility of comprehending spiritual matters without the gift of the Spirit. They also underline the doctrinal and regional fragmentation of the church during the decay and breakup of the Western Roman Empire between 300 and 600 a.d. By 787 a.d., no fewer than seven councils had convened to try to solve the theological arguments.

The Latin Fathers

The theology of the Western portion of Christendom was strongly influenced by four men of the fourth and early fifth centuries: Ambrose, Jerome, John Chrysostom, and Augustine, known collectively as the Latin Fathers.

As bishop of Milan, Ambrose (Circa 340–397) struggled to proclaim and maintain the independence of the church from the encroachments of the state.

Jerome (Circa 345–420) is remembered as the scholarly ascetic who translated the Bible into the Latin version (the Vulgate) that is still used by the Roman Catholic Church.

After years as a monk, John Chrysostom (347–Circa 407) became the most eloquent preacher in the early church (Chrysostom meaning “golden mouth”).

Augustine (354–430), bishop of Hippo in North Africa, wrote several works: The Confessions, revealing his own life in the light of God’s grace; The City of God, setting forth his philosophy of history as the dichotomy between the kingdom of man and the kingdom of God; and On the Trinity, giving final form to the Western church’s teaching of the divine Trinity. Heavily influenced by paganism, Augustine expounded a view of man and God that was hardly complimentary to either.

Conquest and Conversion

For five hundred years after the death of Augustine the Western church was ravaged and desolated by the decay of the protective Roman Empire, by the ensuing invasions from the north (Goths, Vandals, Saxons, Franks, and Vikings), and by the conquests of a vigorous new religion from the Middle East—Islam. Carried throughout Arabia, Mesopotamia, Persia, Syria, Palestine, North Africa, and into Europe through the Iberian peninsula, Islam spread until, by the middle of the eighth century, half of Christendom had come under Islamic rule. Christianity survived, however, though weakened and reduced, and began the slow process of recovering its losses and conquering the conquerors. Step by step, the barbarian invaders were converted to Christianity: the Franks first, then the Anglo-Saxons, the Frisians, and the other Germans. Goths, Lombards, and Burgundians were assimilated into Latin Christendom, as were the vagrant Norsemen. By the end of the eleventh century, Christian crusaders were returning to the East to “redeem” the Holy Land.

A Professional Clergy

Perhaps the most significant change during those “dark ages” was the complete split between the Eastern and Western churches, and the rise of a professional, hierarchical clergy in the West, culminating in the powerful papacy.

The growth of papal power was slow but inexorable. In Constantine’s time, the bishop of Rome was only one of many bishops, with no more authority in the church as a whole than the bishops of Alexandria, Antioch, or Constantinople. But by the thirteenth century, as pope, he boldly proclaimed his supremacy over all the world and its kingdoms.

Constantine and each of his immediate successors had been head of the church—making it an imperial theocracy that continued in the East until 1453. The bishops of Rome, however, contested the imperial supremacy and pronounced their own “primacy” on the ground that Rome was the “Apostolic See,” the center established by the apostle Peter.

In the fifth century Roman bishops began using the title pope (father) to emphasize their superiority to other bishops, a position strongly asserted by Leo I “The Great” (440–61) and expanded by several strong-willed successors. By the middle of the eighth century, when Pope Stephen II sought and received the protection of the Frankish king, the papacy had fully freed itself from imperial authority and resumed its climb to Europeanwide power.

The medieval church was governed by an intricate hierarchical system consisting of the pope at the top, archbishops and bishops in the middle, and parish priests at the bottom. In addition to their jurisdictional functions, priests administered seven sacraments (baptism, confirmation, marriage, ordination, penance, eucharist, and extreme unction). These sacraments were believed to be the channels by which divine grace was imparted to man.

Religious Orders

Separate from these ecclesiastical officers was another group who provided educational and social services and encouraged certain ascetic and personal expressions of Christian piety. These were the orders of monks and nuns, whose lives were regulated by their respective orders, and who took upon themselves formal vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

Medieval monasticism had evolved through a long history, beginning in the third century with early hermits like St. Anthony, who took literally Christ’s injunction to the rich young man to “go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor.” (Matt. 19:21.) Later monks lived communally in monasteries under strict rules, attempting to live in the world but not be of it.

Another kind of religious order, the mendicant friars, came into being in the thirteenth century. Rather than secluding themselves in monasteries, they sought to carry the Christian message by teaching and good deeds.

The first of these orders was the Franciscan, or Friars Minor, founded in Italy by St. Francis of Assisi (1182–1226). Francis’s own life was one of simple and sensitive devotion to God and unselfish service to mankind. A kind-hearted and gentle man, he urged others to love God and neighbors, to forgive freely, and to abstain from all vices of the flesh.

The Dominican Order, or Friars Preachers, was founded by a Spanish priest and student, St. Dominic (Dominic de Guzman, 1170–1221). The mission of this order was to preach to the weak in spirit, to convert the non-Christians, and to teach repentance to the wayward.

Reaction against the Clergy

Many wayward souls did respond to Dominic’s efforts, but others believed the church possessed neither the true gospel nor the authority of God. Such a religious group was the Cathari (“pure ones”) of southern France (known also as Albigenses, after the city of Albi which was their center).

The Cathari, like the earlier Manichaeans, believed the material world was evil and only the spiritual realm was good. They accepted the New Testament (being from God), but they rejected the Old Testament (inspired by Jehovah, creator of the wicked world) along with many teachings and interpretations of the Roman church, including the sacraments. They sharply criticized the growing wealth and power of the clergy. Politics and economic jealousies soon entered the picture until a full-scale crusade was launched against them in 1209.

Another movement branded as heretical was the Waldenses, followers of Peter Waldo (Valdez) of Lyon. The Waldenses, like the Cathari, also spread across southeastern France, northern Spain, northern Italy, and southern Germany. They went in simple garb, two by two without purse or script, teaching their version or the gospel to all who would listen. Forbidding oaths and rejecting masses and prayers for the dead, they soon came under condemnation, and like the Cathari (with whom they disagreed), they suffered persecution and death.

The presence of these and other heresies in the medieval church gave added incentive to the development of “scholastic” arguments for refuting doctrinal error and unbelief. Scholasticism developed in conjunction with the rise of the universities and provided a broad philosophical base for the verification of church dogmas.

This introduction of reason and logic into Christian theology, to serve as an adjunct rather than an enemy to faith, was one of the triumphs of medieval thought. The greatest of the schoolmen was Thomas Aquinas (1225–74), a Dominican teacher whose Summa Theologica, a masterpiece of scholastic reasoning making great use of Aristotelian logic, overcame the apparent conflicts between natural and revealed thought and provided logical proofs of Christian doctrines for the people of the time.

Corruption and Disillusionment

But logic was no more effective than the sword in maintaining religious unity when the leadership of the church itself was steeped in error and engrossed in sin. Of course, not all of the clergy were unworthy. Many priests and monks were sincere, hard-working, and honest; but too many of them were not. By the fourteenth century clerical corruption and abuse were widespread. Absenteeism, venality, concubinage, and slothfulness were common among prelates at every level.

Unfortunately, involved as it was with “high politics,” competing with the secular rulers, the papacy did little to retard this process of deterioration. When Pope Boniface VIII issued the bull (or edict) Unam Sanctum in 1302, which reiterated the papal claim to universal supremacy, he not only infuriated the French king but also alienated many others. Consequently, the Roman see was abolished and the papacy was transplanted to Avignon, in France, where the King could keep a close watch on it. Seventy years later the Great Schism began—a succession of rival popes at Avignon and Rome each denouncing and excommunicating the other, while corruption and confusion ran rampant.

Meanwhile, most honest believers were bewildered and disillusioned. The church was an integral part of their lives and promised the only recognizable path to their salvation. Yet in many ways it was a remote, even hostile, stranger to them.

In a very real sense there were three Catholic churches, and only one of these touched the lives of people in a meaningful way. There was the church of the upper clergy (especially the bishops and cardinals), vying for influence and prestige in a world of power and violence. There was the church of the scholastics and monks, where doctrines were more highly esteemed than morals. And there was the devotional church of the fifty million lay members whose contact with religion came through the mass and other sacraments, and through pilgrimages, prayers, rosaries, relics, and intercessional appeals to the Virgin Mary and to early saints.

Reforms

During the Renaissance (from about 1350–1550), pressures mounted to reform the church and reduce its abuses. This was not the first genuine attempt at reformation. In the tenth century, a revitalization of the monastic system was triggered at the monastery of Cluny, north of Lyon. The cluniac reforms, stressing service, obedience, and piety, had a wide effect which was renewed two hundred years later by Bernard of Clairvaux and the Cistercians.

Even the papacy felt these fresh winds of reform under the indomitable Hildrebrand (Pope Gregory VII, 1073–85), but it did not last. Frequently during the next four centuries pious and well-meaning clergy tried to eliminate abuses within their own jurisdictions, but the problems were usually too interrelated to be successfully attacked piecemeal. Churchwide action was needed but was not forthcoming.

Many people turned to mysticism both for personal catharsis and for churchwide spiritualization. Some formed into societies, such as the Friends of God in the Rhineland and the Brethren of the Common Life in the Netherlands. From one of these groups came the most influential devotional book of the Renaissance, Thomas a Kempis’ Imitation of Christ.

Some of these mystics were sainted (St. Bridget of Sweden, St. Catherine of Siena, San Bernardino of Siena, and San Giovanni Capistrano), while others were charged with heresy. John Wyclif of Oxford and John Hus of Prague were among the latter.

During the final years of the Great Schism (1378–1415), as the divided papacy continued to degenerate, the cry was increasingly heard to convene a general council of the church. This movement gained momentum until it boldly asserted that the supreme governing body of the church was not the pope but a general council representing all Christendom.

The Council of Constance thus convened in 1414. During the next three years it deposed all three rival popes; chose a new one of its own (intended to be a figurehead); charged, heard, condemned, and then brutally killed John Hus; and hesitatingly approached the task of reforming the church “in head and members.”

Yet it did not accomplish its goals. A newly established Renaissance papacy quickly regained its position of primacy. The execution of Hus, instead of ending heresy, caused the Hussites to take up arms for the next half century, devastating much of central and eastern Europe. For the council, reform of the church soon became a dead issue.

It was not a dead issue, however, for all those who saw and were offended by the continuing corruption. Among the more outspoken of these were the Renaissance humanists, men whose devotion to the church was not compromised by their open criticism of its abuses.

Humanism was mainly a scholarly and literary movement whose admiration of classical languages and culture made it suspect in the eyes of many churchmen. The humanists were critical of scholasticism because of its irrelevance, and were vigorously opposed to the immoral lives of the clergy. “What point is there in your being showered with holy water if you do not wipe away the inward pollution from your heart?” chided Erasmus, the greatest of the humanists. “You venerate the saints and delight in touching their relics, but you despise the best one they left behind, the example of a holy life.”

Sir Thomas More echoed that sentiment in his Utopia and in other writings. The humanists held a more optimistic view of human nature and the dignity of man than did the theologians, and placed more trust in the words of scripture than in the subsequent commentaries of the scholastics. Yet they did not wish to harm the church nor divide it; they hoped to unite and strengthen it. To do that, they advocated study, prayer, and a thorough reformation of the lives of the clergy.

Protestantism

One of the clergy, an Augustinian monk and doctor of theology named Martin Luther, was less disturbed by the profusion of immoral conduct (although he condemned that too) than by what he called “the deliberate silence regarding the world of Truth, or else its adulteration.”

In a desperate endeavor to attain salvation through the conscientious performance of meritorious works prescribed by the church, Luther concluded that no man can merit salvation, that it is a gift of God given freely to whom he wills, not as a reward for good deeds but according to divine pleasure. By this simple pronouncement, Luther launched the Protestant Reformation and began the process that would lead first to a split and then a complete fragmentation of Christianity.

If mankind does not need works, indulgences, or sacraments for salvation, he reasoned, then the entire hierarchical system of the Roman church is superfluous and perverse. Indeed, he declared, the pope is not only a hoax, he is the very anti-Christ! Leaning heavily on Augustine’s definition of “original sin,” which declared all mankind to be wicked, depraved, lustful, and an enemy to God, Luther expounded the idea of salvation by grace alone (sola gratia), whereby God chooses some, regardless of their works, to repentance, faith, and salvation through Jesus Christ. Thus redeemed from their own wickedness, the “true believers”—the invisible church of Christ—become righteous doers of good for the right reasons.

Lutheranism spread into many states of Germany and beyond into Scandinavia and eastern Europe. Others quickly took up the Bible to proclaim similar views. Luther believed that no matter how many people read the scriptures, they would all reach the same conclusion if they used good reason and followed their conscience.

But, alas, it was not so. Some groups refuted clerical and monastic vows, others destroyed images, while still others, such as the “Zwichau prophets,” declared the immediate advent of the Lord.

In Switzerland, Ulrich Zwingli renounced the tithe, repudiated clerical celibacy, and abolished the mass. In England Henry VIII rejected the pope and declared himself “the only supreme head in earth of the Church of England.”

John Calvin, a lawyer-theologian from France, carried Protestant doctrines to their logical extreme in his Institutes of the Christian Religion, unabashedly pronouncing the predestination of the elect to salvation and the rest to damnation. At Geneva he established a tightly organized theocracy from which ardent pastors and teachers carried Calvinism into France, the Netherlands, England, Scotland, Germany, Bohemia, and Poland, thus providing the principal theological base of Puritanism, Presbyterianism, Congregationalism, and Dutch, French, and German Reformed faiths.

From the eddies of this Protestant upheaval other groups of reformers emerged. Some of these were called Anabaptists (rebaptizers) because they rejected the practice of infant baptism practiced by both Catholics and Protestants and proclaimed instead baptism by immersion, following conversion and repentance, as a sign of entrance into God’s kingdom.

They usually referred to themselves as “brethren,” or “saints.” Because they came largely from the lower classes, believed in a complete separation of church and state (including refusal to take civil oaths, bear arms, or pay taxes), and had extreme beliefs about the end of the world, they are frequently spoken of as the Radical Reformers. But for the most part they were peaceful and devout followers of Christ.

They believed in a restitution of the primitive church with its organization and communal life. They had no paid ministry, believed that every believer received divine help in understanding the word of God, and rejected the Protestant doctrine of salvation by grace alone, teaching instead salvation by faith and works.

Because they were so different, and their theory of church and state considered dangerous to society, they were feared and ruthlessly persecuted by Catholic and Protestant alike. Most of those who survived did so by fleeing to the east where, under the looser jurisdiction of the rulers of Moravia and Poland, they retained their unique identity and devotion.

Obviously, the Protestant Reformation did not reform the church; it fractured and divided it. Christendom was hopelessly fragmented by the middle of the sixteenth century. Recrimination, persecution, and bloodshed followed. Sincere Catholic reformers—men like Bishop Matteo Giberti and Cardinal Gasparo Contarini—could not prevent the Counter Reformation from over-reacting to the Protestant threat. The Inquisition was revived in a vain effort to wipe out heresy.

Even Ignatius Loyola’s new religious order, the Jesuits, founded in 1540 to teach the young and convert the heathen, was soon turned into an instrument for fighting Protestantism. The council of Trent (which ended in 1563) hardened the lines of religious division, and the Papal Index of Prohibited Books further constricted Christian thought. In a few years the spread of Protestantism was checked, but at an enormous cost.

Still the proliferation of new faiths within Protestantism continued. The rigors of Calvinism in the Netherlands soon generated a reaction there in the form of Arminianism, which tried to moderate the harshness of absolute predestination and “irresistible grace” with a more liberal interpretation of God’s foreknowledge and man’s free will.

In Germany, after the Thirty Years War (1618–48) had taken its gruesome toll, a movement known as Pietism deepened the spiritual life of many Lutherans by cultivating high moral standards and promoting organized works of charity and service.

And in England, George Fox (1624–91) founded the remarkable Society of Friends, known popularly as the Quakers, resembling the earlier Anabaptists in many ways: spiritual revelation, non-professional ministry, rejection of oaths, titles, and war. True Christians, they felt, will be known by their fruits—a consecrated, simple, spiritual life.

While all of these movements met with immediate distrust, anger, and violence, eventually even the fanaticism of religious war subsided and in the pluralism of post-Reformation Europe religious toleration began slowly to appear.

The Enlightenment

That progress toward toleration was aided in the eighteenth century by the spirit of the Enlightenment, particularly the rise of rationalism and “natural religion” (or Deism). According to Deist views, God exists; he created the world, which is then governed by its own natural laws. God should be respected and praised, and men should repent of their sins and do good to one another. The emphasis throughout was on virtue and conduct instead of theology. How foolish it is, noted Voltaire, the most famous of the French Deists, for men to torture and kill one another over the definition of a word or the phrasing of a creed,

Reason and morality were the watchwords of “Enlightened” society. Yet something essential to Christianity was missing in this rational religion: the intimacy of God and the divinity of Christ. Christianity without the miracles of the birth, Resurrection, and Atonement is not Christianity at all. The new humanitarianism can only be praised—for too long it had been ignored by partisan theologians—but the Deist rejection of theology, although making room for greater toleration of different Christian sects, was a criticism of Christianity itself.

Partly in response to the Deist influence came a wide-ranging evangelical awakening, especially in England. It stressed the fundamentals of Christian devotion and particularly the renewal and revitalization of life which results from a full commitment to Christ.

A notable product of this evangelicalism was a new society called Methodism, whose chief architects were John (1703–91) and Charles (1707–77) Wesley. Methodist emphasis upon “conversion” and cultivation of the Christian life, including service to others, contributed materially to a revival of Christianity and to the active promotion of social reforms, such as the abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807.

And thus for seventeen centuries Christianity struggled through trials of every kind, from persecution to prosperity, from harmony to discord and disintegration, groping for answers to questions asked and unasked. As its proponents ignored or misunderstood the teachings of Christ and his apostles, Christianity foundered. As they responded to glimmers of that original light, Christianity during these centuries helped prepare men and nations for the fulness of the restored gospel.

Showing posts with label Christianity. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Christianity. Show all posts

Friday, October 10, 2008

“Mom, Are We Christians?”

Gary J. Coleman, “‘Mom, Are We Christians?’,” Ensign, May 2007, 92–94

I am a devout Christian who is exceedingly fortunate to have greater knowledge of the true “doctrine of Christ” since my conversion to the restored Church.

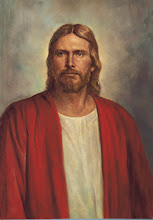

Christianity celebrates the life and ministry of Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God the Eternal Father. Christian churches with great variations of doctrine dot the land the world over. When 14-year-old Cortnee, a daughter of a mission president, entered a new high school as a freshman, she was asked by classmates if she was a Christian. They scoffed at her response that she was a Mormon, a common reference to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Upon arriving home she asked her mother, “Mom, are we Christians?”

Growing up in my family, we lived as devout members of another Christian faith. I was baptized a member of that church shortly after my birth. Our family went to church each week. For many years my brothers and I assisted the pastors who conducted our Sunday services. I was taught the importance of family prayer as our family prayed together each day. I thought that someday I would enter the full-time ministry in my church. There was no question in our minds that we could define ourselves as devout Christians.

When I was a university student, however, I became acquainted with the members and teachings of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a Christian faith centered on the Savior. I began to learn about the doctrine of the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ in these latter days. I learned truths that I had not known before that changed my life and how I viewed the gospel. After much studying, prayer, and faith, I chose to embrace beautiful restored truths found only in this Church.

The first restored truth that I learned was the nature of the Godhead. The true Christian doctrine that the Godhead consists of three separate beings was known in biblical times. God bore witness of Jesus, His Only Begotten Son, on several occasions. He spoke at Jesus’s baptism: “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.”1 Jesus Himself testified of God, His Father, when He said, “And this is life eternal, that they might know thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom thou hast sent.”2 After Jesus’s death and Resurrection, we learn that Stephen, “he, being full of the Holy Ghost, looked up stedfastly into heaven, and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing on the right hand of God, and said, Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of man standing on the right hand of God.”3 What a dramatic testimony of the Godhead from that disciple of Christ.

The knowledge of God and His physical separateness from His Son and the Holy Ghost was lost after the death of Christ and His Apostles. Confusion and false doctrines about the Godhead were fashioned out of the Nicene Creed and Constantinople councils, where men declared that instead of three separate beings, the Godhead was three persons in one God, or the Trinity. Just as Christian Protestant reformers struggled with these creeds of men, I did as well. The teachings about the Trinity that I learned in my youth were incomprehensible to me.

However, when I was introduced to the glorious truths of the First Vision experienced by the Prophet Joseph Smith, it was a stunning awakening for me to finally understand the truth about the nature of God the Eternal Father and His Only Begotten Son. Joseph declared: “I saw two Personages, whose brightness and glory defy all description, standing above me in the air. One of them spake unto me, calling me by name and said, pointing to the other—This is My Beloved Son. Hear Him!”4 This heavenly vision restored the wondrous yet plain and precious knowledge of God and His Son to the earth again, dispelling at once the teachings I had learned about the Trinity.

I know that heaven-sent revelations have replaced the gross errors of man-made doctrines concerning the Godhead. I know that God is our Heavenly Father. His Son, Jesus Christ, is my Savior. The Holy Ghost testifies of the Father and the Son. I express my profound gratitude to God for introducing the resurrected Lord Jesus Christ to mankind in these last days. The Savior lives; He has been seen; He has spoken; He directs the work of His Church through apostles and prophets today. What magnificent truths He has taught as the Good Shepherd who continues to look after His sheep.

The second restored truth I learned as an investigator of this Church was the reality of additional scripture and revelation. The prophet Isaiah saw in vision a book that he proclaimed was part of “a marvellous work and a wonder.”5 I testify that the Book of Mormon: Another Testament of Jesus Christ is that book. It is a sacred record written by prophets of God to persuade all people to come unto Christ, and it helps to reveal the gospel of Jesus Christ in its fulness. The Book of Mormon tells of prophets and other faithful members of the Church who took upon themselves the name of Christ, even before the Savior’s birth.6 This book tells of the resurrected Christ teaching men what they must do to gain peace in this life and eternal salvation in the world to come. What could be more Christian than seeking to take His name upon ourselves and follow His counsel to become like Him?

President Gordon B. Hinckley has said, “I cannot understand why the Christian world does not accept this book.”7 I first read the Book of Mormon at the age of 21. I then asked God if it was true. The truth of it was manifested unto me by the comforting power of the Holy Ghost.8 I know that the Book of Mormon is a second testament of Jesus Christ. I join my testimony with the prophets of this sacred book to declare that “we talk of Christ, we rejoice in Christ, we preach of Christ, we prophesy of Christ.”9 I am deeply grateful for every word that He has spoken and for every word He continues to speak as He quenches our thirst with living water.

Another restored truth of the gospel I became acquainted with was the restoration of priesthood authority, or the power to act in God’s name. Former prophets and apostles, such as Elijah, Moses, John the Baptist, Peter, James, and John, have been sent by God and Christ in our day to restore the holy priesthood of God. Every priesthood holder in this Church can trace his priesthood authority directly to Jesus Christ. Men now possess the keys to establish the Church so that we can come unto Christ and partake of His eternal ordinances of salvation.10 I testify that this is the Church of Jesus Christ—the only church authorized with true priesthood authority to exercise the keys of salvation through sacred ordinances.

Cortnee asked, “Mom, are we Christians?” As a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, you are a Christian, and I am too. I am a devout Christian who is exceedingly fortunate to have greater knowledge of the true “doctrine of Christ”11 since my conversion to the restored Church. These truths define this Church as having the fulness of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Like other members of the Church, I now understand the true nature of the Godhead, I have access to additional scripture and revelation, and I can partake of the blessings of priesthood authority. Yes, Cortnee, we are Christians, and I testify of these truths in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Notes

1. Matthew 3:17.

2. John 17:3.

3. Acts 7:55–56.

4. Joseph Smith—History 1:17.

5. See Isaiah 29:14; see also vv. 11–12, 18.

6. See Alma 46:14–16.

7. The Marvelous Foundation of Our Faith,” Liahona and Ensign, Nov. 2002, 81.

8. See Moroni 10:4–5.

9. 2 Nephi 25:26.

10. See D&C 2; 13; 110; 112:32.

11. 2 Nephi 31:2; see also 3 Nephi 11:31–36.

I am a devout Christian who is exceedingly fortunate to have greater knowledge of the true “doctrine of Christ” since my conversion to the restored Church.

Christianity celebrates the life and ministry of Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God the Eternal Father. Christian churches with great variations of doctrine dot the land the world over. When 14-year-old Cortnee, a daughter of a mission president, entered a new high school as a freshman, she was asked by classmates if she was a Christian. They scoffed at her response that she was a Mormon, a common reference to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Upon arriving home she asked her mother, “Mom, are we Christians?”

Growing up in my family, we lived as devout members of another Christian faith. I was baptized a member of that church shortly after my birth. Our family went to church each week. For many years my brothers and I assisted the pastors who conducted our Sunday services. I was taught the importance of family prayer as our family prayed together each day. I thought that someday I would enter the full-time ministry in my church. There was no question in our minds that we could define ourselves as devout Christians.

When I was a university student, however, I became acquainted with the members and teachings of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a Christian faith centered on the Savior. I began to learn about the doctrine of the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ in these latter days. I learned truths that I had not known before that changed my life and how I viewed the gospel. After much studying, prayer, and faith, I chose to embrace beautiful restored truths found only in this Church.

The first restored truth that I learned was the nature of the Godhead. The true Christian doctrine that the Godhead consists of three separate beings was known in biblical times. God bore witness of Jesus, His Only Begotten Son, on several occasions. He spoke at Jesus’s baptism: “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.”1 Jesus Himself testified of God, His Father, when He said, “And this is life eternal, that they might know thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom thou hast sent.”2 After Jesus’s death and Resurrection, we learn that Stephen, “he, being full of the Holy Ghost, looked up stedfastly into heaven, and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing on the right hand of God, and said, Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of man standing on the right hand of God.”3 What a dramatic testimony of the Godhead from that disciple of Christ.

The knowledge of God and His physical separateness from His Son and the Holy Ghost was lost after the death of Christ and His Apostles. Confusion and false doctrines about the Godhead were fashioned out of the Nicene Creed and Constantinople councils, where men declared that instead of three separate beings, the Godhead was three persons in one God, or the Trinity. Just as Christian Protestant reformers struggled with these creeds of men, I did as well. The teachings about the Trinity that I learned in my youth were incomprehensible to me.

However, when I was introduced to the glorious truths of the First Vision experienced by the Prophet Joseph Smith, it was a stunning awakening for me to finally understand the truth about the nature of God the Eternal Father and His Only Begotten Son. Joseph declared: “I saw two Personages, whose brightness and glory defy all description, standing above me in the air. One of them spake unto me, calling me by name and said, pointing to the other—This is My Beloved Son. Hear Him!”4 This heavenly vision restored the wondrous yet plain and precious knowledge of God and His Son to the earth again, dispelling at once the teachings I had learned about the Trinity.

I know that heaven-sent revelations have replaced the gross errors of man-made doctrines concerning the Godhead. I know that God is our Heavenly Father. His Son, Jesus Christ, is my Savior. The Holy Ghost testifies of the Father and the Son. I express my profound gratitude to God for introducing the resurrected Lord Jesus Christ to mankind in these last days. The Savior lives; He has been seen; He has spoken; He directs the work of His Church through apostles and prophets today. What magnificent truths He has taught as the Good Shepherd who continues to look after His sheep.

The second restored truth I learned as an investigator of this Church was the reality of additional scripture and revelation. The prophet Isaiah saw in vision a book that he proclaimed was part of “a marvellous work and a wonder.”5 I testify that the Book of Mormon: Another Testament of Jesus Christ is that book. It is a sacred record written by prophets of God to persuade all people to come unto Christ, and it helps to reveal the gospel of Jesus Christ in its fulness. The Book of Mormon tells of prophets and other faithful members of the Church who took upon themselves the name of Christ, even before the Savior’s birth.6 This book tells of the resurrected Christ teaching men what they must do to gain peace in this life and eternal salvation in the world to come. What could be more Christian than seeking to take His name upon ourselves and follow His counsel to become like Him?

President Gordon B. Hinckley has said, “I cannot understand why the Christian world does not accept this book.”7 I first read the Book of Mormon at the age of 21. I then asked God if it was true. The truth of it was manifested unto me by the comforting power of the Holy Ghost.8 I know that the Book of Mormon is a second testament of Jesus Christ. I join my testimony with the prophets of this sacred book to declare that “we talk of Christ, we rejoice in Christ, we preach of Christ, we prophesy of Christ.”9 I am deeply grateful for every word that He has spoken and for every word He continues to speak as He quenches our thirst with living water.

Another restored truth of the gospel I became acquainted with was the restoration of priesthood authority, or the power to act in God’s name. Former prophets and apostles, such as Elijah, Moses, John the Baptist, Peter, James, and John, have been sent by God and Christ in our day to restore the holy priesthood of God. Every priesthood holder in this Church can trace his priesthood authority directly to Jesus Christ. Men now possess the keys to establish the Church so that we can come unto Christ and partake of His eternal ordinances of salvation.10 I testify that this is the Church of Jesus Christ—the only church authorized with true priesthood authority to exercise the keys of salvation through sacred ordinances.

Cortnee asked, “Mom, are we Christians?” As a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, you are a Christian, and I am too. I am a devout Christian who is exceedingly fortunate to have greater knowledge of the true “doctrine of Christ”11 since my conversion to the restored Church. These truths define this Church as having the fulness of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Like other members of the Church, I now understand the true nature of the Godhead, I have access to additional scripture and revelation, and I can partake of the blessings of priesthood authority. Yes, Cortnee, we are Christians, and I testify of these truths in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Notes

1. Matthew 3:17.

2. John 17:3.

3. Acts 7:55–56.

4. Joseph Smith—History 1:17.

5. See Isaiah 29:14; see also vv. 11–12, 18.

6. See Alma 46:14–16.

7. The Marvelous Foundation of Our Faith,” Liahona and Ensign, Nov. 2002, 81.

8. See Moroni 10:4–5.

9. 2 Nephi 25:26.

10. See D&C 2; 13; 110; 112:32.

11. 2 Nephi 31:2; see also 3 Nephi 11:31–36.

Labels:

Are Mormons Christians?,

Christianity,

godhead,

trinty

Friday, July 20, 2007

The Plurality of Gods

Actually the real objection in modern Christian churches to the doctrine of deification is often that it implies the existence of more than one God. If human beings can become gods and yet remain distinct beings separate from God, it makes for a universe with many gods. Surely C. S. Lewis realized this implication; so did the early Christian saints. Yet like the Latter-day Saints they did not understand this implication to constitute genuine polytheism.

For both the doctrine of deification and the implied doctrine of plurality of gods, an understanding of the definitions involved is essential. So let's be clear on what Latter-day Saints do not believe. They do not believe that humans will ever be equal to or independent of God. His status in relation to us is not in any way compromised. There is only one source of light, knowledge, and power in the universe. If through the gospel of Jesus Christ and the grace of God we receive the fulness of God (Eph. 3:19) so that we also can be called gods, humans will never become "ultimate" beings in the abstract, philosophical sense. That is, even as they sit on thrones exercising the powers of gods, those who have become gods by grace remain eternally subordinate to the source of that grace; they are extensions of their Father's power and agents of his will. They will continue to worship and serve the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost forever, and will worship and serve no one and nothing else.

If the Latter-day Saints had chosen to refer to such glorified beings as "angels" instead of "gods," it is unlikely anyone outside the LDS church would have objected to the doctrine per se. It seems that it is only the term that is objectionable. And yet the scriptures themselves often use the word god in this limited sense to refer to nonultimate beings.

For example, in Ps. 8 the word gods (Hebrew elohim) is used in reference to the angels: "What is man, that thou art mindful of him? and the son of man, that thou visitest him? For thou hast made him a little lower than the angels [elohim], and hast crowned him with glory and honour." (Vv. 4-5.) Though the Hebrew reads "gods" (elohim), translators and commentators from the Septuagint on, including the author of Hebrews in the New Testament, have understood the expression to refer to the angels (see Heb. 2:7). The term gods is here applied to beings other than God. Deuteronomy 10: 17, Josh. 22:22, and Ps. 136:2 all insist that God is a "God of gods." Clearly this doesn't mean that there are divine competitors out in the cosmos somewhere; rather, these passages probably also refer to the angels in their divinely appointed roles. If the angels can, in some sense, be considered divine beings because they exercise the powers of God and act as his agents, then the one God they serve is correctly considered a "God of gods." Scholars have long known, and the Dead Sea Scrolls and other literature of the period have now proven, that the Jews in Jesus' day commonly referred to the angels as "gods" (Hebrew elim or elohim) in this nonultimate sense.fn This is not because the Jews were polytheists, but because they used the term god in a limited sense to refer to other beings associated with God whom he allowed the privilege of exercising divine powers.

But human beings are also called "gods" in scripture, probably for the same reasons that the angels are-they, as well as the angels, can exercise the powers of God and act as his agents. Thus Moses is designated a "god to Pharaoh" (Ex. 7:1). This doesn't mean that Moses had become an exalted or ultimate being, but only that he had been given divine powers and was authorized to represent God to Pharaoh, even to the point of speaking God's word in the first person. If the scriptures can refer to a mortal human being like Moses as a "god" in this sense, then surely immortal human beings who inherit the fulness of God's powers and authority in the resurrection can be understood to be "gods" in the same sense.

In Ex. 21:6 and 22:8-9 human judges are referred to in the Hebrew text as elohim ("gods"). In Ps. 45:6 the king is referred to as an elohim. Human leaders and judges are also referred to as "gods" in the following passage from the book of Psalms: "God standeth in the congregation of the mighty; he judgeth among the gods .... I have said, Ye are gods; and all of you are children of the most High. But ye shall die like men, and fall like one of the princes." (Ps. 82:1,6-7 Jewish and Christian biblical scholars alike have understood this passage as applying the term sods to human beings. According to James S. Ackerman, who is not a Mormon, "the overwhelming majority of commentators have interpreted this passage as referring to Israelite judges who were called 'gods' because they had the high responsibility of dispensing justice according to God's Law."fn

In the New Testament, at John 10:34-36, we read that Jesus himself quoted Ps. 82:6 and interpreted the term gods as referring to human beings who had received the word of God: "Jesus answered them, Is it not written in your law, I said, Ye are gods? If he called them gods, unto whom the word of God came, and the scripture cannot be broken; say ye of him, whom the Father hath sanctified, and sent into the world, Thou blasphemest; because I said, I am the Son of God?" In other words, 'If the scriptures [Ps. 82] can refer to mortals who receive the word of God as "gods," then why get upset with me for merely saying I am the Son of God?' The Savior's argument was effective precisely because the scripture does use the term gods in this limited way to refer to human beings. According to J. A. Emerton, who is also not a Mormon, "most exegetes are agreed that the argu- ment is intended to prove that men can, in certain circumstances, be called gods .... [Jesus] goes back to fundamental principles and argues, more generally, that the word 'god' can, in certain circumstances, be applied to beings other than God himself, to whom he has committed authority."fn

And that, in a nutshell, is the LDS view. Whether in this life or the next, through Christ human beings can be given the powers of God and the authority of God. Those who receive this great inheritance can properly be called gods. They are not gods in the Greek philosophic sense of "ultimate beings," nor do they compete with God, the source of their inheritance, as objects of worship. They remain eternally his begotten sons and daughters -therefore, never equal to him nor independent of him. Orthodox theologians may argue that Latter-day Saints shouldn't use the term gods for nonultimate beings, but this is because the Latter-day Saints' .use of the term violates Platonic rather than biblical definitions. Both in the scriptures and in earliest Christianity those who received the word of God were called gods.

I don't need to repeat here the views of Christian saints and theologians cited above on the doctrine of deification. But it should be noted that for them, as for the Latter-day Saints, the doctrine of deification implied a plurality of "gods" but not a plurality of Gods. That is, it did not imply polytheism. Saint Clement of Alexandria was surely both a monotheist and a Christian, and yet he believed that those who are perfected through the gospel of Christ "are called by the appellation of gods, being destined to sit on thrones with the other gods that have been first installed in their places by the Savior."fn This is good LDS doctrine. If Clement, the Christian saint and theologian, could teach that human beings will be called gods and will sit on thrones with others who have been made gods by Jesus Christ, how in all fairness can Joseph Smith be declared a polytheist and a non-Christian for teaching the same thing?

In harmony with widely recognized scriptural and historical precedents, Latter-day Saints use the term gods to describe those who will, through the grace of God and the gospel of Jesus Christ, receive of God's fulness - of his divine powers and pre-rogatives-in the resurrection. Thus, for Latter-day Saints the question "Is there more than one god?" is not the same as "Is there more than one source of power or object of worship in the universe?" For Latter-day Saints, as for Saint Clement, the answer to the former is yes, but the answer to the latter is no. For Latter-day Saints the term god is a title which can be extended to those who receive the power and authority of God as promised to the faithful in the scriptures; but such an extension of that title does not challenge, limit, or infringe upon the ultimate and absolute position and authority of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

When anti-Mormon critics interpret Exodus ?: 1, Deut. 10:1 ?, Ps. 8:5 (in Hebrew), Ps. 45:6, Ps. 82:6, or John 10:34-36, they go to great lengths to clarify that these scriptures use the term god in a limited sense and that therefore they do not involve any polytheism-there may be more than one "god," but there is only one God. When they discuss Latter-day Saint writings that use the term god in the same sense, however, the critics seldom offer the same courtesy. Instead they disallow any limited sense in which the term gods can be used when that term occurs in LDS sources, thereby distorting and misinterpreting our doctrine, and then accuse us of being "polytheists" for speaking of "gods" in a sense for which there are valid scriptural and historical precedents.

Other Christian saints, theologians, and writers-both ancient and modern-have believed human beings can become "gods" but have not been accused of polytheism, because the "gods" in this sense were viewed as remaining forever subordinate to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Since this is also the doctrine of the Latter-day Saints, they also ought to enjoy the same defense against the charge of polytheism. Since these other Christians and the Latter-day Saints share the same doctrine, they should share the same fate; either make polytheist heretics of the saints, theologians, and writers in question, or allow the Latter-day Saints to be considered worshippers of the one true God.

President Snow often referred to this couplet as having been revealed to him by inspiration during the Nauvoo period of the Church. See, for example, Deseret Weekly 49 (3 November 1894): 610; Deseret Weekly 57 (8 October 1898): 513; Deseret News 52 (15 June 1901): 177; and Journal History of the Church, 20 July 1901, p. 4.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies, bk. 5, pref.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 4.38. Cp. 4.11 (2): "But man receives progression and increase towards God. For as God is always the same, so also man, when found in God, shall always progress towards God."

Clement of Alexandria, Exhortation to the Greeks, 1.

Clement of Alexandria, The Instructor, 3.1. See also Clement, Stro-mateis, 23.

Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 124.

Athanasius, Against the Arians, 1.39, 3.34.

Athanasius, De Inc., 54.

Augustine, On the Psalms, 50.2. Augustine insists that such individuals are gods by grace rather than by nature, but they are gods nevertheless.

Richard P. McBrien, Catholicism, 2 vols. (Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1980), 1:146, 156; emphasis in original.

Symeon Lash, "Deification," in The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology, ed. Alan Richardson and John Bowden (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1985), pp. 147-48.

For a longer treatment of this subject, see Jules Gross, La divinisa-tion du chrétien d'aprè les pères grecs (Paris: J. Gabalda, 1938).

Paul Crouch, "Praise the Lord," Trinity Broadcasting Network, 7 July 1986.

Robert Tilton, God's Laws of Success (Dallas: Word of Faith, 1983), pp. 170-71.

Kenneth Copeland, The Force of Love (Fort Worth: Kenneth Copeland, n.d.), tape BCC-56.

Kenneth Copeland, The Power of the Tongue (Fort Worth: Kenneth Copeland, n.d.), p. 6. I am not arguing that these evangelists are mainline evangelicals (though they would insist that they are), only that they are Protestants with large Christian followings.

C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses, rev. ed. (New York: Macmillan, Collier Books, 1980), p. 18.

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: Macmillan, 1952; Collier Books, 1960), p. 153. Cp. p. 164, where Lewis describes Christ as "finally, if all goes well, turning you permanently into a different sort of thing; into a new little Christ, a being which, in its own small way, has the same kind of life as God; which shares in His power, joy, knowledge and eternity." See also C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters, rev. ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1982), p. 38, where the tempter Screwtape complains that God intends to fill heaven with "little replicas of Himself."

Lewis, Mere Christianity, p. 154.

Lewis, Mere Christianity, pp. 174-75. For a more recent example of the doctrine of deification in modern, non-LDS Christianity, see M. Scott Peck, The Road Less Traveled (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978) pp. 269-70: "For no matter how much we may like to pussyfoot around it, all of us who postulate a loving God and really think about it even- tually come to a single terrifying idea: God wants us to become Himself (or Herself or Itself). We are growing toward godhood."

Most critics are surprised to know how highly the thinking of C. S. Lewis is respected by Latter-day Saint readers.

See, for example, John Strugnell, The Angelic Liturgy at Qumran -4 Q Serek Sirot 'Olat Hassabat in Supplements to Vetus Testamenturn VII [Congress Volume, Oxford 1959], (Leiden: Brill, 1960), pp. 336-38, or A. S. van der Woude, "Melchisedek als himmlische Erlösergestalt in den neuge-fundenen eschatologischen Midraschim aus Qumran Höhle XI," Oudtestamentische Studiën 14 ( 1965): 354-73.

James S. Ackerman, "The Rabbinic Interpretation of Ps. 82 and the Gospel of John," Harvard Theological Review 59 (April 1966): 186.

J. A. Emerton, "The Interpretation of Ps. 82 in John 10," Journal of Theological Studies 11 (April 1960): 329, 332. This was also the view of Saint Augustine in writing of this passage in On the Psalms, 50.2: "It is evident, then, that he has called men 'gods,' who are deified by his grace" (cf. also 97.12).

Clement of Alexandria, Stromateis, 7.10.

(Stephen E. Robinson, Are Mormons Christians? [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1991],

For both the doctrine of deification and the implied doctrine of plurality of gods, an understanding of the definitions involved is essential. So let's be clear on what Latter-day Saints do not believe. They do not believe that humans will ever be equal to or independent of God. His status in relation to us is not in any way compromised. There is only one source of light, knowledge, and power in the universe. If through the gospel of Jesus Christ and the grace of God we receive the fulness of God (Eph. 3:19) so that we also can be called gods, humans will never become "ultimate" beings in the abstract, philosophical sense. That is, even as they sit on thrones exercising the powers of gods, those who have become gods by grace remain eternally subordinate to the source of that grace; they are extensions of their Father's power and agents of his will. They will continue to worship and serve the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost forever, and will worship and serve no one and nothing else.

If the Latter-day Saints had chosen to refer to such glorified beings as "angels" instead of "gods," it is unlikely anyone outside the LDS church would have objected to the doctrine per se. It seems that it is only the term that is objectionable. And yet the scriptures themselves often use the word god in this limited sense to refer to nonultimate beings.

For example, in Ps. 8 the word gods (Hebrew elohim) is used in reference to the angels: "What is man, that thou art mindful of him? and the son of man, that thou visitest him? For thou hast made him a little lower than the angels [elohim], and hast crowned him with glory and honour." (Vv. 4-5.) Though the Hebrew reads "gods" (elohim), translators and commentators from the Septuagint on, including the author of Hebrews in the New Testament, have understood the expression to refer to the angels (see Heb. 2:7). The term gods is here applied to beings other than God. Deuteronomy 10: 17, Josh. 22:22, and Ps. 136:2 all insist that God is a "God of gods." Clearly this doesn't mean that there are divine competitors out in the cosmos somewhere; rather, these passages probably also refer to the angels in their divinely appointed roles. If the angels can, in some sense, be considered divine beings because they exercise the powers of God and act as his agents, then the one God they serve is correctly considered a "God of gods." Scholars have long known, and the Dead Sea Scrolls and other literature of the period have now proven, that the Jews in Jesus' day commonly referred to the angels as "gods" (Hebrew elim or elohim) in this nonultimate sense.fn This is not because the Jews were polytheists, but because they used the term god in a limited sense to refer to other beings associated with God whom he allowed the privilege of exercising divine powers.

But human beings are also called "gods" in scripture, probably for the same reasons that the angels are-they, as well as the angels, can exercise the powers of God and act as his agents. Thus Moses is designated a "god to Pharaoh" (Ex. 7:1). This doesn't mean that Moses had become an exalted or ultimate being, but only that he had been given divine powers and was authorized to represent God to Pharaoh, even to the point of speaking God's word in the first person. If the scriptures can refer to a mortal human being like Moses as a "god" in this sense, then surely immortal human beings who inherit the fulness of God's powers and authority in the resurrection can be understood to be "gods" in the same sense.

In Ex. 21:6 and 22:8-9 human judges are referred to in the Hebrew text as elohim ("gods"). In Ps. 45:6 the king is referred to as an elohim. Human leaders and judges are also referred to as "gods" in the following passage from the book of Psalms: "God standeth in the congregation of the mighty; he judgeth among the gods .... I have said, Ye are gods; and all of you are children of the most High. But ye shall die like men, and fall like one of the princes." (Ps. 82:1,6-7 Jewish and Christian biblical scholars alike have understood this passage as applying the term sods to human beings. According to James S. Ackerman, who is not a Mormon, "the overwhelming majority of commentators have interpreted this passage as referring to Israelite judges who were called 'gods' because they had the high responsibility of dispensing justice according to God's Law."fn

In the New Testament, at John 10:34-36, we read that Jesus himself quoted Ps. 82:6 and interpreted the term gods as referring to human beings who had received the word of God: "Jesus answered them, Is it not written in your law, I said, Ye are gods? If he called them gods, unto whom the word of God came, and the scripture cannot be broken; say ye of him, whom the Father hath sanctified, and sent into the world, Thou blasphemest; because I said, I am the Son of God?" In other words, 'If the scriptures [Ps. 82] can refer to mortals who receive the word of God as "gods," then why get upset with me for merely saying I am the Son of God?' The Savior's argument was effective precisely because the scripture does use the term gods in this limited way to refer to human beings. According to J. A. Emerton, who is also not a Mormon, "most exegetes are agreed that the argu- ment is intended to prove that men can, in certain circumstances, be called gods .... [Jesus] goes back to fundamental principles and argues, more generally, that the word 'god' can, in certain circumstances, be applied to beings other than God himself, to whom he has committed authority."fn

And that, in a nutshell, is the LDS view. Whether in this life or the next, through Christ human beings can be given the powers of God and the authority of God. Those who receive this great inheritance can properly be called gods. They are not gods in the Greek philosophic sense of "ultimate beings," nor do they compete with God, the source of their inheritance, as objects of worship. They remain eternally his begotten sons and daughters -therefore, never equal to him nor independent of him. Orthodox theologians may argue that Latter-day Saints shouldn't use the term gods for nonultimate beings, but this is because the Latter-day Saints' .use of the term violates Platonic rather than biblical definitions. Both in the scriptures and in earliest Christianity those who received the word of God were called gods.

I don't need to repeat here the views of Christian saints and theologians cited above on the doctrine of deification. But it should be noted that for them, as for the Latter-day Saints, the doctrine of deification implied a plurality of "gods" but not a plurality of Gods. That is, it did not imply polytheism. Saint Clement of Alexandria was surely both a monotheist and a Christian, and yet he believed that those who are perfected through the gospel of Christ "are called by the appellation of gods, being destined to sit on thrones with the other gods that have been first installed in their places by the Savior."fn This is good LDS doctrine. If Clement, the Christian saint and theologian, could teach that human beings will be called gods and will sit on thrones with others who have been made gods by Jesus Christ, how in all fairness can Joseph Smith be declared a polytheist and a non-Christian for teaching the same thing?

In harmony with widely recognized scriptural and historical precedents, Latter-day Saints use the term gods to describe those who will, through the grace of God and the gospel of Jesus Christ, receive of God's fulness - of his divine powers and pre-rogatives-in the resurrection. Thus, for Latter-day Saints the question "Is there more than one god?" is not the same as "Is there more than one source of power or object of worship in the universe?" For Latter-day Saints, as for Saint Clement, the answer to the former is yes, but the answer to the latter is no. For Latter-day Saints the term god is a title which can be extended to those who receive the power and authority of God as promised to the faithful in the scriptures; but such an extension of that title does not challenge, limit, or infringe upon the ultimate and absolute position and authority of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

When anti-Mormon critics interpret Exodus ?: 1, Deut. 10:1 ?, Ps. 8:5 (in Hebrew), Ps. 45:6, Ps. 82:6, or John 10:34-36, they go to great lengths to clarify that these scriptures use the term god in a limited sense and that therefore they do not involve any polytheism-there may be more than one "god," but there is only one God. When they discuss Latter-day Saint writings that use the term god in the same sense, however, the critics seldom offer the same courtesy. Instead they disallow any limited sense in which the term gods can be used when that term occurs in LDS sources, thereby distorting and misinterpreting our doctrine, and then accuse us of being "polytheists" for speaking of "gods" in a sense for which there are valid scriptural and historical precedents.

Other Christian saints, theologians, and writers-both ancient and modern-have believed human beings can become "gods" but have not been accused of polytheism, because the "gods" in this sense were viewed as remaining forever subordinate to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Since this is also the doctrine of the Latter-day Saints, they also ought to enjoy the same defense against the charge of polytheism. Since these other Christians and the Latter-day Saints share the same doctrine, they should share the same fate; either make polytheist heretics of the saints, theologians, and writers in question, or allow the Latter-day Saints to be considered worshippers of the one true God.

President Snow often referred to this couplet as having been revealed to him by inspiration during the Nauvoo period of the Church. See, for example, Deseret Weekly 49 (3 November 1894): 610; Deseret Weekly 57 (8 October 1898): 513; Deseret News 52 (15 June 1901): 177; and Journal History of the Church, 20 July 1901, p. 4.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies, bk. 5, pref.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 4.38. Cp. 4.11 (2): "But man receives progression and increase towards God. For as God is always the same, so also man, when found in God, shall always progress towards God."

Clement of Alexandria, Exhortation to the Greeks, 1.

Clement of Alexandria, The Instructor, 3.1. See also Clement, Stro-mateis, 23.

Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 124.

Athanasius, Against the Arians, 1.39, 3.34.

Athanasius, De Inc., 54.

Augustine, On the Psalms, 50.2. Augustine insists that such individuals are gods by grace rather than by nature, but they are gods nevertheless.

Richard P. McBrien, Catholicism, 2 vols. (Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1980), 1:146, 156; emphasis in original.

Symeon Lash, "Deification," in The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology, ed. Alan Richardson and John Bowden (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1985), pp. 147-48.

For a longer treatment of this subject, see Jules Gross, La divinisa-tion du chrétien d'aprè les pères grecs (Paris: J. Gabalda, 1938).

Paul Crouch, "Praise the Lord," Trinity Broadcasting Network, 7 July 1986.

Robert Tilton, God's Laws of Success (Dallas: Word of Faith, 1983), pp. 170-71.

Kenneth Copeland, The Force of Love (Fort Worth: Kenneth Copeland, n.d.), tape BCC-56.

Kenneth Copeland, The Power of the Tongue (Fort Worth: Kenneth Copeland, n.d.), p. 6. I am not arguing that these evangelists are mainline evangelicals (though they would insist that they are), only that they are Protestants with large Christian followings.

C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses, rev. ed. (New York: Macmillan, Collier Books, 1980), p. 18.

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: Macmillan, 1952; Collier Books, 1960), p. 153. Cp. p. 164, where Lewis describes Christ as "finally, if all goes well, turning you permanently into a different sort of thing; into a new little Christ, a being which, in its own small way, has the same kind of life as God; which shares in His power, joy, knowledge and eternity." See also C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters, rev. ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1982), p. 38, where the tempter Screwtape complains that God intends to fill heaven with "little replicas of Himself."

Lewis, Mere Christianity, p. 154.

Lewis, Mere Christianity, pp. 174-75. For a more recent example of the doctrine of deification in modern, non-LDS Christianity, see M. Scott Peck, The Road Less Traveled (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978) pp. 269-70: "For no matter how much we may like to pussyfoot around it, all of us who postulate a loving God and really think about it even- tually come to a single terrifying idea: God wants us to become Himself (or Herself or Itself). We are growing toward godhood."

Most critics are surprised to know how highly the thinking of C. S. Lewis is respected by Latter-day Saint readers.

See, for example, John Strugnell, The Angelic Liturgy at Qumran -4 Q Serek Sirot 'Olat Hassabat in Supplements to Vetus Testamenturn VII [Congress Volume, Oxford 1959], (Leiden: Brill, 1960), pp. 336-38, or A. S. van der Woude, "Melchisedek als himmlische Erlösergestalt in den neuge-fundenen eschatologischen Midraschim aus Qumran Höhle XI," Oudtestamentische Studiën 14 ( 1965): 354-73.

James S. Ackerman, "The Rabbinic Interpretation of Ps. 82 and the Gospel of John," Harvard Theological Review 59 (April 1966): 186.

J. A. Emerton, "The Interpretation of Ps. 82 in John 10," Journal of Theological Studies 11 (April 1960): 329, 332. This was also the view of Saint Augustine in writing of this passage in On the Psalms, 50.2: "It is evident, then, that he has called men 'gods,' who are deified by his grace" (cf. also 97.12).

Clement of Alexandria, Stromateis, 7.10.

(Stephen E. Robinson, Are Mormons Christians? [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1991],

The Doctrine of Deification

It is indisputable that Latter-day Saints believe that God was once a human being and that human beings can become gods. The famous couplet of Lorenzo Snow, fifth President of the LDS church, states:

As man now is, God once was;

As God now is, man may be.fn

It has been claimed by some that this is an altogether pagan doctrine that blasphemes the majesty of God. Not all Christians have thought so, however. In the second century Saint Irenaeus, the most important Christian theologian of his time, said much the same thing as Lorenzo Snow:

If the Word became a man,

It was so men may become gods.fn

Indeed, Saint Irenaeus had more than this to say on the subject of deification:

Do we cast blame on him [God] because we were not made gods from the beginning, but were at first created merely as men, and then later as gods? Although God has adopted this course out of his pure benevolence, that no one may charge him with discrimination or stinginess, he declares, "I have said, Ye are gods; and all of you are sons of the Most High."... For it was necessary at first that nature be exhibited, then after that what was mortal would be conquered and swallowed up in immortality.fn

Also in the second century, Saint Clement of Alexandria wrote, "Yea, I say, the Word of God became a man so that you might learn from a man how to become a god"fn-almost a paraphrase of Lorenzo Snow's statement. Clement also said that "if one knows himself, he will know God, and knowing God will become like God .... His is beauty, true beauty, for it is God, and that man becomes a god, since God wills it. So Heraclitus was right when he said, 'Men are gods, and gods are men."fn

Still in the second century, Saint Justin Martyr insisted that in the beginning men "were made like God, free from suffering and death," and that they are thus "deemed worthy of becoming gods and of having power to become sons of the highest."fn

In the early fourth century Saint Athanasius-that tireless foe of heresy after whom the orthodox Athanasian Creed is named-also stated his belief in deification in terms very similar to those of Lorenzo Snow: "The Word was made flesh in order that we might be enabled to be made gods .... Just as the Lord, putting on the body, became a man, so also we men are both deified through his flesh, and henceforth inherit everlasting life."fn On another occasion Athanasius stated, "He became man that we might be made divine"fn-yet another parallel to Lorenzo Snow's expression.

Finally, Saint Augustine himself, the greatest of the Christian Fathers, said: "But he himself that justifies also deifies, for by justifying he makes sons of God. 'For he has given them power to become the sons of God' [John 1:12]. If then we have been made sons of God, we have also been made gods."fn

Notice that I am citing only unimpeachable Christian authorities here-no pagans, no Gnostics. All five of the above writers were not just Christians, and not just orthodox Christians -they were orthodox Christian saints. Three of the five wrote within a hundred years of the period of the Apostles, and all five believed in the doctrine of deification. This doctrine was a part of historical Christianity until relatively recent times, and it is still an important doctrine in some Eastern Orthodox churches. Those who accuse the Latter-day Saints of making up the doc- trine simply do not know the history of Christian doctrine. In one of the best works on Catholicism, Father Richard P. McBrien states that a fundamental principle of orthodoxy in the patristic period was to see "the history of the universe as the history of divinization and salvation." As a result the Fathers concluded, according to McBrien, that "because the Spirit is truly God, we are truly divinized by the presence of the Spirit."fn

In The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology, which is not a Mormon publication, the following additional information can be found in the article titled, "Deification":

Deification (Greek theosis) is for Orthodoxy the goal of every Christian. Man, according to the Bible, is 'made in the image and likeness of God'.... It is possible for man to become like God, to become deified, to become god by grace. This doctrine is based on many passages of both OT and NT (e.g. Ps. 82 (81).6; 2 Pet. 1.4 and it is essentially the teaching both of St Paul, though he tends to use the language of filial adoption (cf. Rom. 8.9-17 Gal. 4.5-7 and the Fourth Gospel (cf. 17.21-23).